I want to say Thank You to a few folks who have made this book possbile.

First, my wife Alison, who has been my loyal support since the day we met in High School in 1967.

Secondly, Andreas Huggel the founder of the project and Luis and Dan who have worked tirelessly with me since 2017.

Exiv2 contributors (in alphabetical order): Abhinav, Alan, Alex, Andreas (both of them), Arnold, Ben, Christoph, Gilles, Kevin, Leo, Leonardo, Mahesh, Michał, Mikayel, Miloš, Nehal, Neils, Peter, Phil, Rosen, Sridhar, Thomas, Tuan …. and others who have contributed to Exiv2.

File Detectives: Phil Harvey, Dave Coffin, Laurent Clévy.

And our cat Lizzie. Sadly, Lizzie was put to sleep on 2021-02-13.

This book is about Image Metadata and Exiv2 Architecture.

Image Metadata is the information stored in a digital image in addition to the image itself. Data such as the camera model, date, time, location and camera settings are stored. To my knowledge, no book has been written about this important technology.

Exiv2 Architecture is about the Exiv2 library and command-line application which implements cross-platform code in C++ to read, modify, insert and delete items of metadata. I’ve been working on this code since 2008 and, as I approach my 70th birthday, would like to document my knowledge in the hope that the code will be maintained and developed by others in future.

At the moment, the book is work in progress and expected to be finished in 2021. Exiv2 v0.27.4 shipped on schedule on 2021-04-30 and the working copy of this book in available on exiv2.org.

There is no plan to have the book printed or commercially published.

I first became interested in metadata because of a trail conversation with Dennis Connor in 2008. Dennis and I ran frequently together in Silicon Valley and Dennis was a Software Development Manager in a company that made GPS systems for Precision Agriculture. I had a Garmin Forerunner 201 Watch. We realised that we could extract the GPS data from the watch in GPX format, then merge the position into photos. Today this is called “GeoTagging” and is supported by many applications.

I said “Oh, it can’t be too difficult to do that!”. And here we are more than a decade later still working on the project. The program geotag.py was completed in about 6 weeks. Most of the effort went into porting Exiv2 and pyexiv2 to Visual Studio and macOS. Both Exiv2 and pyexiv2 were Linux only at that time.

The program samples/geotag.cpp is a command-line application to geotag photos and I frequently use this on my own photographs. Today, I have a Samsung Galaxy Watch which uploads runs to Strava. I download the GPX from Strava. The date/time information in the JPG is the key to search for the position data. The GPS tags are created and saved in the image.

In 2008, I chose to implement this in python because I wanted to learn the language. Having discovered exiv2 and the python wrapper pyexiv2, I set off with enthusiasm to build a cross-platform script to run on Windows (XP, Visual Studio 2003), Ubuntu Linux (Hardy Heron 2008.04 LTS) and MacOS-X (32 bit Tiger 10.4 on a big-endian PPC). After I finished, I emailed Andreas. He responded in less than an hour and invited me to join Team Exiv2. Initially, I provided support to build Exiv2 with Visual Studio.

Incidentally, later in 2008, Dennis offered me a contract to port his company’s Linux code to Visual Studio to be used on a Windows CE Embedded Controller. 1 million lines of C++ were ported from Linux in 6 weeks. I worked with Dennis for 4 years on all manner of GPS related software development.

https://clanmills.com/articles/gpsexiftags/

I have never been employed to work on Metadata. I was a Senior Computer Scientist at Adobe for more than 10 years, however I was never involved with XMP or Metadata.

By 2012, Andreas was losing interest in Exiv2. Like all folks, he has many matters which deserve his time. A family, a business, biking and other pursuits. From 2012 until 2017, I supported Exiv2 mostly alone. I had lots of encouragement from Alan and other occasional contributors. Neils did great work on lens recognition and compatibility with ExifTool. Ben helped greatly with WebP support and managed the transition of the code from SVN to GitHub. Phil (of ExifTool fame) has always been very supportive and helpful.

I must also mention our adventures with Google Summer of Code and our students Abhinav, Tuan and Mahesh. GSoC is a program at Google to sponsor students to contribute to open source projects. 1200 Students from around the world are given a bounty of $5000 to contribute 500 hours to a project during summer recess. The projects are supervised by a mentor. Exiv2 is considered to be part of the KDE family of projects. Within KDE, there is a sub-group of Graphics Applications and Technology. We advertised our projects, the students wrote proposals and some were accepted by Google on the Recommendation of the KDE/Graphics group.

In 2012, Abhinav joined us and contributed the Video read code and was mentored by Andreas. In 2013, Tuan joined us and contributed the WebReady code and was mentored by me. Mahesh also joined us to contribute the Video write code and was mentored by Abhinav.

I personally found working with the students to be enjoyable and interesting. I retired from work in 2014 and returned to England after 15 years in Silicon Valley. In 2016, Alison and I had a trip round the world and spent a day with Mahesh in Bangalore and with Tuan in Singapore. We were invited to stay with Andreas and his family. We subsequently went to Vietnam to attend Tuan’s wedding in 2017.

After v0.26 was released in 2017, Luis and Dan started making contributions. They have made many important contributions in the areas of security, test and build. In 2019, Kevin joined us. He discovered and fixed some security issues.

The current release of Exiv2 is v0.27.4 and shipped on 2021-04-30. I hope v1.00 will be released in 2021-12-15. Further “dot” releases of v0.27 and v1.00 may be published for security fixes in future.

The Libre Graphics Meeting was scheduled to take place in May 2020 in Rennes, France. I intended to conduct a workshop on Image Metadata and Exiv2 Architecture. This book was being written to be used in that presentation. Regretfully, the Covid-19 crisis caused the postponement of LGM.

I started working on Exiv2 to implement GeoTagging. As the years have passed, I’ve explored most of the code. I’ve added new capability such as support for ICC profiles, metadata-piping and file-debugging. I’ve done lots of work on the build, test suite and documentation. I’ve talked to users all over the world and closed several hundred issues and feature requests. Over the years, I’ve met users in India, Singapore, Armenia, the USA and the UK. I’ve attended 2 Open-Source Conferences. It’s been an adventure and mostly rewarding. When I answer questions, it’s rare for users to acknowledge my response. Almost nobody says “Thank You, Robin”.

In July 2017 we received our first security CVE. Not a pleasant experience. The security folks started hitting us with fuzzed files. These are files which violate format specifications and can cause the code to crash. We responded with v0.27 which will have regular “dot” releases to provide security fixes. Managing frequent releases and user correspondence consumes lots of my time.

In parallel with “the dots”, major work was done by Luis, Dan and Rosie to prepare Exiv2 for the future on the ‘master’ branch. Due to the covid crisis, this project was terminated and the C++11 code has been ported to branch ‘main’.

I’m delighted by the work done by Dan, Luis and Kev to deal with the assault of the security people. I believe we are responding effectively. None-the-less, they have dominated development of Exiv2 for several years. Many ideas could not be pursued because security consumed our engineering resources.

The code is in good shape, our release process is solid and we have comprehensive user documentation. As photography develops, there will be many new cameras and image formats. Exiv2 Video support is weak and was deprecated in v0.27. It will be removed in v1.00. One day a contributor will re-engineer the video code.

A long standing project for Exiv2 is a unified metadata container. There is an implementation of this in the unstable branch of the SVN repository. Currently we have three containers for Exif, Iptc and Xmp. This is clumsy. We also have a restriction of one image per file. Perhaps both restrictions have a common solution. The unified metadata container will be included in Exiv2 v1.00.

The toolset used in Software Engineering evolves with time. C++ has been around for about 35 years and, while many complain about it, I expect it will out-live most of us. None-the-less, languages which are less vulnerable to security issues may lead the project to a re-write in a new language such as Rust. I hope this book provides the necessary understanding of metadata to support such an undertaking.

The most common issue raised by users concerns lens recognition. For v0.26, I added the Configuration File feature to enable users to modify lens recognition on their computer. While this is helpful, many users would like Exiv2 to deal with this perfectly, both now and in the future.

I intended to make a proposal at LGM in Rennes in May 2020 concerning this matter. Both Exiv2 and ExifTool can extract metadata from an image into a .EXV file. I would propose to implement a program to read the .EXV and return the Lens. That program will have an embedded programming language with the rules to identify the lens. The scripts will be ascii files which can be updated. It will be called M2Lscript (MetaData to Lens Script), pronounced “MillsScript”. The M2Lscript interpreter will be available as a command-line application, a perl module (for ExifTool), a C++ library (for linking into exiv2) and perhaps a python module.

In this way, new lens definitions can be written in M2Lscript without touching anything in Exiv2 or ExifTool.

I will not be able to work on both Exiv2 and M2Lscript simulateously. When a new maintainer takes responsibility for Exiv2, I will retire. M2Lscript would be my swansong technology project. However, the C-19 crisis postponed LGM in 2020. I don’t have the energy to continue with open-source. This book is my final contribution.

This book is my gift and legacy to Exiv2. I hope Exiv2 will continue to exist long into the future. This book is being written to document my discoveries about Image Metadata and Exiv2 Architecture. However, I want to avoid a cut'n'paste of information already in the project documentation. This book is an effort to collect my knowledge of this code into a single volume. Many topics in this book are discussed in more detail in the issue history stored in Redmine and GitHub. I hope this book helps future maintainers to understand Exiv2, solve issues and develop the code for years to come.

I wish you a happy adventure in the world of Image Metadata. If you’d like to discuss matters concerning this book, please open an issue on GitHub and share your thoughts with Team Exiv2.

This book is copyright and licensed under GNU GPLv2. https://www.gnu.org/licenses/old-licenses/gpl-2.0.html

Attention is drawn to the possibility that some elements of this document may be the subject of patent rights. Robin Mills and/or the Exiv2 Project and/or the Exiv2 Contributors shall not be held responsible for identifying any or all such patent rights.

I’ve had a lot of fun making this book. Most of the time was spent on the code, however getting the book into good shape for the web and print has been fun. The graphics were drawn using OmniGraffle 6.6.2 on my MacBook Pro. Exporting the drawings to PNG is very awkward in Omni-graffle. I use the export a region WITH transparency. Left 0 Top 0 Width 19.5 Height 19.5/15.5. To make the background white: $ convert foo.png -background white -flatten foo.png.

All the documentation for Exiv2 is written in markdown with the exception of the Unix man page exiv2.1 I find markdown easy to use and quickly produces satisfying results.

The book is written in markdown and displayed on my computer with the MacDown Application. When MacDown exports a PDF, he ignores print directives in the style sheet, he does not support page numbering and the links are ineffective. To my taste, the text size of pages is too large when printed on A4.

I used a modified version of this style sheet: ~/Library/Application Support/MacDown/Styles/GitHub2.css. I changed the fonts to be Helvetica in the titles and Palatino in the body. I thought about using the Exiv2 logo font which is Albertus Medium. I decided to adopt the ubiquitous Palatino. Code is set in Consolas in both the graphics and the in-line code snippets in the text.

@media print {

h1,h2 { page-break-before: always; }

h3,h4 { page-break-after: never; }

}I get MacDown to export HTML to IMaEA.html. I open IMaEA.html in Safari and print it into a PDF file with a page size of 275x389mm. This preserves the aspect ratio √2/1 of ISO-Standard pages. Safari has a option to add page number and date to every page. I get Safari to save the print in PDF (it’s 275x388). The printing system on macOS has a Paper Handling feature to scale the print to fit a page size and I set that to A4. I save the PDF from the print system and the result is a beautiful A4 document with all the links working and scaled to fit A4.

I have to manually update the page numbers in the table of contents. If Exiv2 ever supports PDF, I’ll probably be able to script that! I only do that when I intend to publish the file as it’s tedious.

The final step is to take the PDF to the local print shop to be printed and bound.

Incidentally, I investigated adding a clickable Exiv2 logo to every page of the PDF and found this very useful open-source program pdfstamp: url = https://github.com/CrossRef/pdfstamp.git

PDF documents work in point sizes (72/inch) so A4 pages 297x210mm = 842x596pt. The origin is in the lower left.

$ java -jar pdfstamp.jar -v -i ~/gnu/exiv2/team/book/exiv2.png -l 30,30 -u https://exiv2.org -pp 2-74 ~/clanmills/exiv2/book/IMaEA.pdf -o .

$ java -jar pdfstamp.jar -v -d 8000 -i ~/gnu/exiv2/team/book/exiv2-large.png -l 550,30 -u https://exiv2.org -pp 2-75 ~/clanmills/exiv2/book/IMaEA.pdf -o . We could use this to add page labels (date/time/title) to every page (except the front page).

I also investigated doing this in the style-sheet. I tried Safari, Chrome and Firefox with varying success. Then I read this: https://www.smashingmagazine.com/2015/01/designing-for-print-with-css/.

The prince product fully supports HTML->PDF with @media print in the style sheet and works really well. They offer a free/unrestricted license for non-commercial use.

I tried prince and was very pleased with the result. When you ask prince to create the PDF, you can specify page-size and style sheet. I’ve set up IMaEA.css with the builtin page size of 275x389.

$ prince --page-size='275mm 389mm' --style ~/gnu/exiv2/team/book/pdf-styles.css IMaEA.html

$ prince --type IMaEA.css IMaEA.htmlThe date that appears at the center-bottom of every page (except the first) is in the style sheet. You could change that with sed of course. Setting the date from the computer clock would be fine for an automatic reporting application. Better to use static text as we might want to say “Exiv2 v0.27.3 2020-06-30” or the like.

The resulting PDF is beautiful and not watermarked by prince, although they put a postit on the front page. That’s OK. They deserve credit for their outstanding work and free license.

However, prince rendered the code snippets as plain pre-formatted text and didn’t provide the beautiful formatting and syntax colouring provide by MacDown and which is printed in the PDF generated by Safari.

So, I decided that the Safari/PDF was the best PDF and I tweaked the PDF in three ways using SodaPDF. I fixed the title and dates on every page. I fixed the “goto page#” PDF links which were mysteriously off by one page, and I added a PDF Table of Contents. The result is a beautiful document which looks great on the tablet (in HTML or PDF), great on the computer and beautiful when printed.

Thank You for reading my book.

The following summaries of the file formats are provided to help you to understand both this book and the Exiv2 code. The Standard Specifications should be consulted for more detail.

I’ve made a summary of every file format supported by Exiv2 and hope you find that useful. There are an absurd number of Graphics File Formats. I have a copy somewhere of the O'Reilly book. I got it in 1996 and it has 1000+ pages. Since then there have been many more invented. It’s a software mess. In the early days, many formats were local to a few users in a University and escaped to a wider audience. However the never ending stream of new standards is horrible. Canon have several different Raw formats such as CRW, CR2 and CR3.

A good model for an image is to think of it as a container. It’s like a directory on the disk. The directory can hold files with different formats and the directory is recursive as it can contain a directory of more files. Almost every graphics format since TIFF in 1992 is a container.

The good news however is that file formats come in families which are:

| Family | Description | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| TIFF | You must learn Tiff thoroughly to understand metadata | TIFF, DNG, NEF, ICC, CR2, ORF, RAF, DCP,PEF |

| JIFF | JPEG Image File Format Linked list of 64k segments |

JPEG, EXV |

| PNG | Another popular format Linked list of chunks |

PNG |

| CIFF | Camera Image File Format. Dave Coffin parse.c decodes CRW | CRW |

| BMFF | Base Media File Format. Based on the .mp4 format | MP4, CR3, AVIF, HEIC, JP2, JXL |

| RIFF | Resource Interchange File Format | WEBP, AVI |

| GIF | Graphics Image Format | GIF |

| BMP | Windows BMP never has XMP, IPTC or Exif metadata. Version5 may include an ICC profile. |

BMP |

The Metadata is defined by standards which also define how to embed the data in the image.

| Standard | Description |

|---|---|

| Exif | EXchangeable Image Format. This is encoded as a TIFF sub-file |

| IPTC | International Press Telecommunications Council |

| ICC | Internation Colour Consortium The ICC Profile is similar to TIFF The ICC Profile is an ICC sub-file. |

| XMP | Adobe XMP is encoded as an XML sub-file |

I suspect the proliferation of formats is caused by the hardware engineers. When hardware people start a new project, they copy the CAD files from the last project and proceed from there. They don’t worry about back-porting changes or compatibility. We have to live with this mess.

There is also the issue of patents. It’s unclear if it’s legal to read a BMFF file which is used by Apple to in HEIC files. I believe it is legal to read BMFF files. It’s illegal to reverse engineer the proprietary encoded data stored in the mdat box a HEIC. Metadata is occasionally compressed (PNG), encrypted (Nikon) or ciphered (Sony).

Here is a useful WikiPedia site that summarises file formats: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Comparison_of_graphics_file_formats

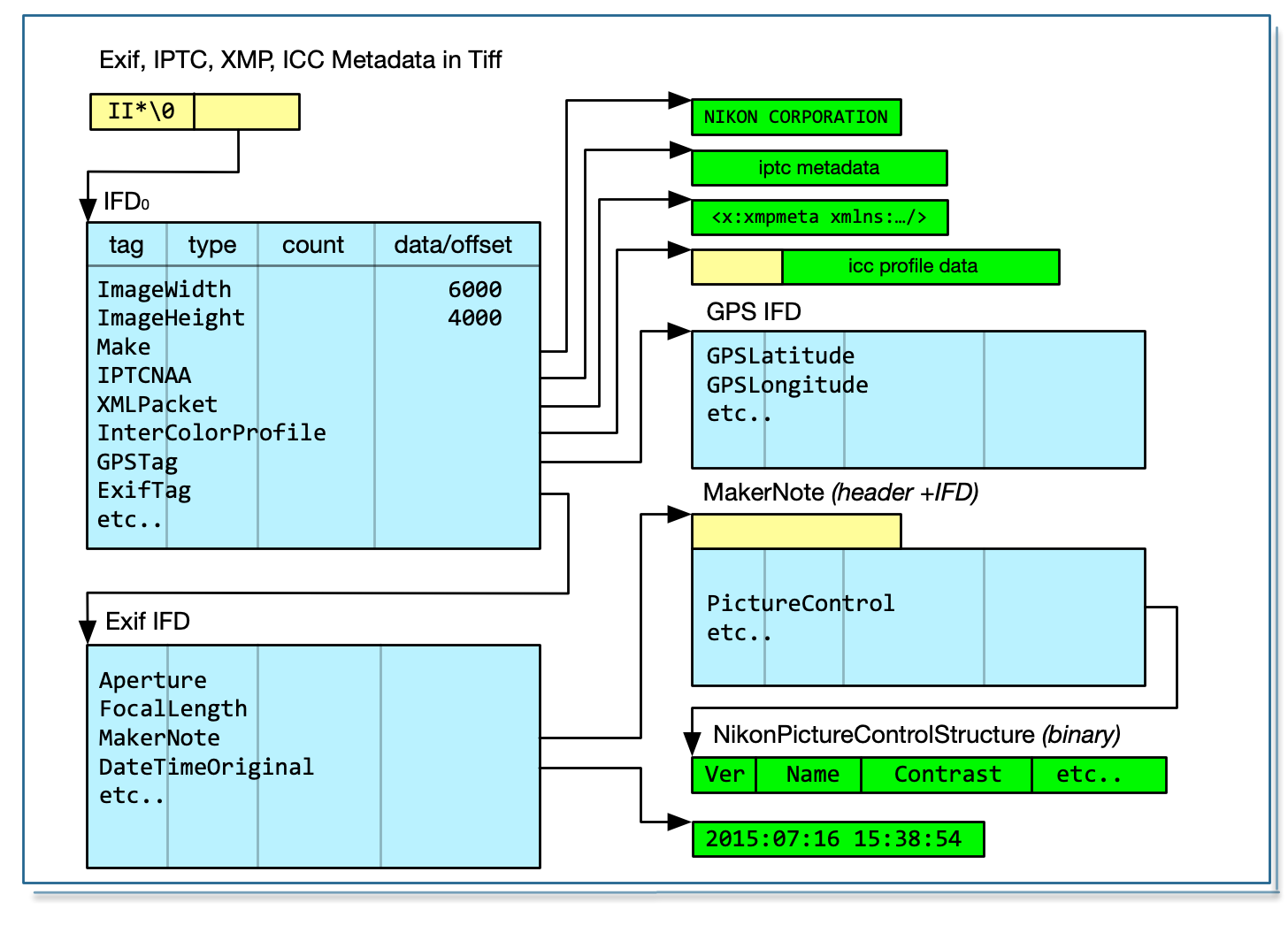

The architecture of TIFF and BigTiff are the same. BigTiff is 64 bit based. So most uint16_t data types become uint32_t and uint32_t become uint64_t. BigTiff has three additional 8 byte types: Long8, SLong8 and Ifd8.

For both TIFF and BigTiff, the magic header is MM (Motorola) for big-endian and II (Intel) for little-endian, followed by a 2-byte integer which must be 42 (ascii *) for Tiff and 43 (ascii +) for BigTiff. These markers are very obvious MM_+ or II*_ when formatted by dmpf.cpp

Both tag and type are uint16_t in TIFF and BigTiff.

The header for TIFF is 8 bytes. It is the magic header followed by a long offset to the first IFD. The header for BigTiff is 16 bytes. It is the magic header followed by 2 shorts (which must be 8,0) and a long8 offset to the first IFD.

| Element | TIFF | BigTiff | Element | TIFF | BigTiff |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Header | XX*_Long | XX+_ 8 0 Long8 | Header | 8 bytes | 16 bytes |

| Marker | * 0x2a = 42 | + 0x2b = 43 | Offset | uint32_t | uint64_t |

| Tag | uint16_t | uint16_t | Entry | 12 bytes | 20 bytes |

| Type | uint16_t | uint16_t | Entries #E | uint16_t | uint64_t |

| Count | uint32_t | uint64_t | Next | uint32_t | uint64_t |

It’s important to understand that Endian can change as we descend into the file. There are images in which there are sub-files whose endian setting is different from the container.

These are defined in the following tags:

$ taglist ALL | grep -e ^Image\.InterColorProfile -e ^Image.XMLPacket | csv -

[Image.XMLPacket] [700] [0x02bc] [Image] [Exif.Image.XMLPacket] [Byte] [XMP Metadata (Adobe technote 9-14-02)]

[Image.InterColorProfile] [34675] [0x8773] [Image] [Exif.Image.InterColorProfile] [Undefined] [...]

693 rmills@rmillsmm-local:~/gnu/exiv2/team/book $

$ These are tiff files. There must be some subtle matters to be handled in these formats, however tvisitor has no trouble running over the files. Allow me to quote directly from Adobe’s document: https://wwwimages2.adobe.com/content/dam/acom/en/products/photoshop/pdfs/dng_spec_1.5.0.0.pdf

A Standard Format

The lack of a standard format for camera raw files creates additional work for camera manufacturers because they need to develop proprietary formats along with the software to process them. It also poses risks for end users. Camera raw formats vary from camera to camera, even those produced by the same manufacturer. It is not uncommon for a camera manufacturer to terminate support for a discontinued camera’s raw format. This means users have no guarantee they will be able to open archived camera raw files in the future.

To address these problems, Adobe has defined a new non-proprietary format for camera raw files. The format, called Digital Negative or DNG, can be used by a wide range of hardware and software developers to provide a more flexible raw processing and archiving workflow. End users may also use DNG as an intermediate format for storing images that were originally captured using a proprietary camera raw format.

TIFF Compatible

DNG is an extension of the TIFF 6.0 format, and is compatible with the TIFF-EP standard. It is possible (but not required) for a DNG file to simultaneously comply with both the Digital Negative specification and the TIFF-EP standard.

I downloaded and installed Adobe’s DNG Convertor and applied it to some NEF files from my Nikon D5300:

.../book/build $ ./tvisitor -pU .../files/DSC_0003.dng

STRUCTURE OF TIFF FILE (II): /Users/rmills/temp/Raw/DSC_0003.dng

address | tag | type | count | offset | value

10 | 0x00fe Exif.Image.NewSubfileType | LONG | 1 | | 1

22 | 0x0100 Exif.Image.ImageWidth | LONG | 1 | | 256

34 | 0x0101 Exif.Image.ImageLength | LONG | 1 | | 171

46 | 0x0102 Exif.Image.BitsPerSample | SHORT | 3 | 734 | 8 8 8

58 | 0x0103 Exif.Image.Compression | SHORT | 1 | | 1

70 | 0x0106 Exif.Image.PhotometricInte.. | SHORT | 1 | | 2

82 | 0x010f Exif.Image.Make | ASCII | 18 | 740 | NIKON CORPORATION

94 | 0x0110 Exif.Image.Model | ASCII | 12 | 758 | NIKON D5300

106 | 0x0111 Exif.Image.StripOffsets | LONG | 1 | | 286218

118 | 0x0112 Exif.Image.Orientation | SHORT | 1 | | 1

130 | 0x0115 Exif.Image.SamplesPerPixel | SHORT | 1 | | 3

142 | 0x0116 Exif.Image.RowsPerStrip | LONG | 1 | | 171

154 | 0x0117 Exif.Image.StripByteCounts | LONG | 1 | | 131328

166 | 0x011c Exif.Image.PlanarConfigura.. | SHORT | 1 | | 1

178 | 0x0131 Exif.Image.Software | ASCII | 37 | 770 | Adobe DNG Converter 12.3 (Macintosh)

190 | 0x0132 Exif.Image.DateTime | ASCII | 20 | 808 | 2020:07:13 14:53:56

202 | 0x014a Exif.Image.SubIFD | LONG | 2 | 828 | 280022 285140

STRUCTURE OF TIFF FILE (II): /Users/rmills/temp/Raw/DSC_0003.dng

address | tag | type | count | offset | value

280024 | 0x00fe Exif.Image.NewSubfileType | LONG | 1 | | 0

280036 | 0x0100 Exif.Image.ImageWidth | LONG | 1 | | 6016

280048 | 0x0101 Exif.Image.ImageLength | LONG | 1 | | 4016

280060 | 0x0102 Exif.Image.BitsPerSample | SHORT | 1 | | 16

280072 | 0x0103 Exif.Image.Compression | SHORT | 1 | | 7

280084 | 0x0106 Exif.Image.PhotometricInte.. | SHORT | 1 | | 32803

280096 | 0x0115 Exif.Image.SamplesPerPixel | SHORT | 1 | | 1

280108 | 0x011c Exif.Image.PlanarConfigura.. | SHORT | 1 | | 1

280120 | 0x0142 Exif.Image.0x142 | LONG | 1 | | 256

280132 | 0x0143 Exif.Image.0x143 | LONG | 1 | | 256

...

280348 | 0xc761 Exif.Image.0xc761 | DOUBLE | 6 | 285092 | 4549338546106269780 4516671190936266 +++

END: /Users/rmills/temp/Raw/DSC_0003.dng

...

706 | 0xc761 Exif.Image.0xc761 | DOUBLE | 6 | 279958 | 4549338546106269780 4516671190936266 +++

718 | 0xc7a7 Exif.Image.0xc7a7 | UBYTE | 16 | 280006 | 51 35 79 139 126 151 164 251 56 72 2 +++

END: /Users/rmills/temp/Raw/DSC_0003.dngI was a little surprised that Adobe appeared to have removed the MakerNote. However, Phil Harvey alerted me to my error. In fact, the tag Exif.DNG.DNGPrivateData is a wrapper around the MakerNote. However the offset to the MakerNote in the Raw image and the DNG are different. So, it’s possible that data in the Raw makernote has been lost by the DNG convertor.

“Undefined” tags are reported by tvisitor in the format: Exif.Image.0xc761 and defined in the specification. For example: C761.H is “Noise Profile” for which the mathematics are explained by Adobe!

It’s possible that there are tags which are unique to CR2 and NEF and tvisitor.cpp is hiding them when the U option is not being used. In the first instance, you are welcome to search the Exiv2 source code to see if there is anything special or unusual being defined or used by the CR2 and NEF handlers.

There is a significant problem with the Tiff format. It’s possible for binary records to hold offsets to significant data elsewhere in the file. This creates two problems. Firstly, when buried in an undocumented MakerNote, we don’t know that the data is an offset. So, when all the blocks move in a rewrite of the file, we can neither relocate the referenced data, nor update the offset. My conclusion is that is almost impossible to garbage collect a tiff file. However, the situation isn’t hopeless. The offset in the Tiff Header defines the location of IFD0. It’s very common that IFD0 is at the end of the file and the reason is obvious. When a Tiff is rewritten by an application, they create IFD0 in memory, then copy it to the end of the file and update the offset in the header. If we are creating IFD0, we can safely reuse the spaced occuped by previous IFD0.

Imperial College have medical imaging Tiff files which are of the order of 100 GigaBytes in length. Clearly we do not want to rewrite such a file to modify a few bytes of metadata. We determine the new IFD0 and write it at end of the file.

When we update a Makernote, we should “edit in place” and avoid relocating the data. Regrettably for a JPEG, that’s almost impossible. As camera manufacturers have higher resolutions and larger displays for review, the manufacturers want to have larger thumbnails. The manufacturers appear to be happy to store the preview somewhere in the JPEG and have a hidden offset in the makernote. This works fine until the image is edited when the preview is lost.

In principle, a Tiff can be garbage collected with a block-map. If we set up a block-map with one bit for every thousand bytes, we can run the IFDs and mark all the blocks in use. When we rewrite the TIFF (well IFD0 actually), we can inspect the block-map to determine a “hole” in the file at which to write. I would not do this. It’s unsafe to over-write anything in a Tiff with the exception of IFD0 and the header offset. The situation with JPEG is more serious. It’s impossible to rewrite the JPEG in place.

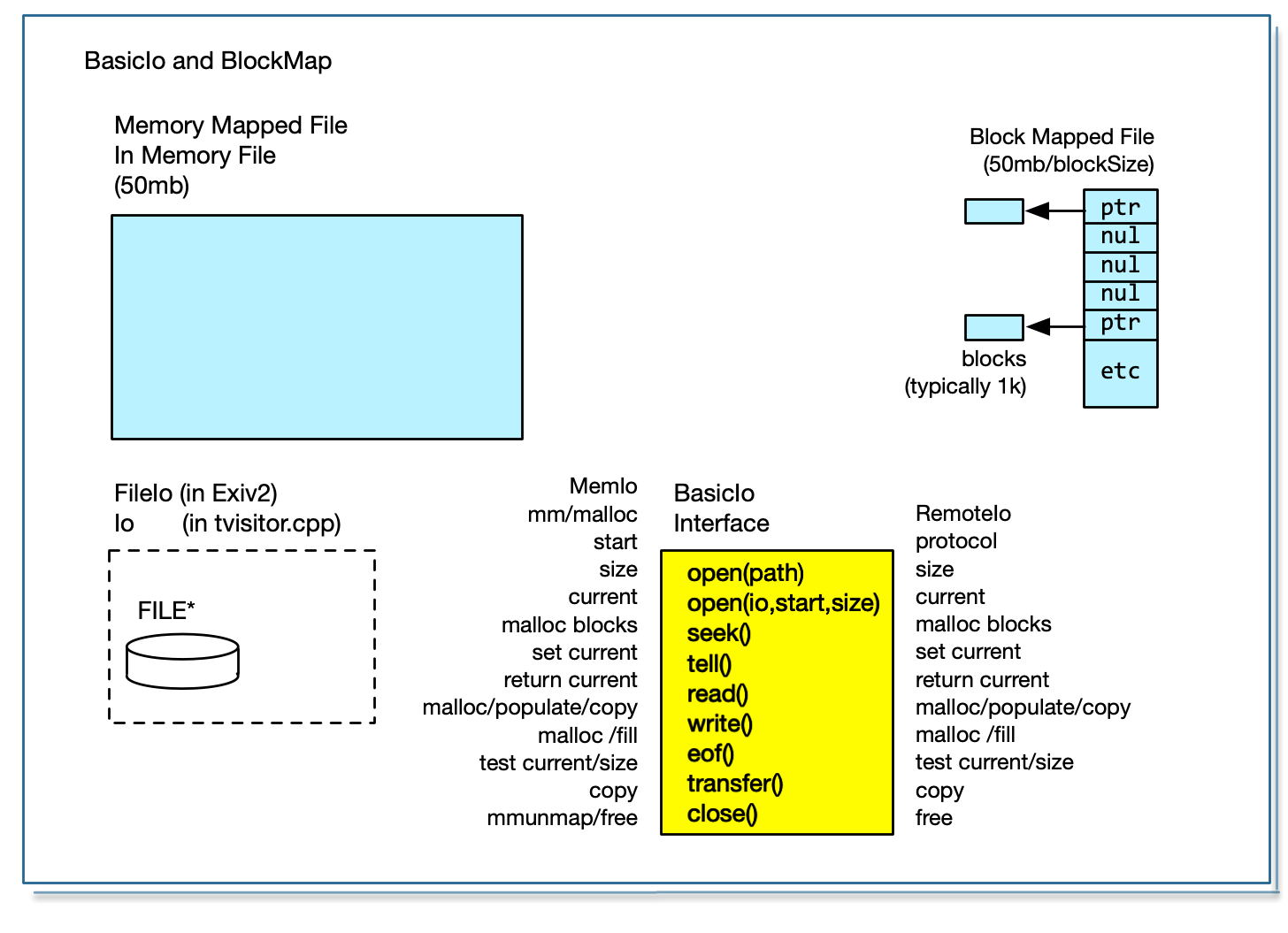

The concept of using a block-map to track known data is used in RemoteIo. We use a block-map to avoid excessive remote I/O by reading data into a cache. We never read data twice. We do not need contiguous memory for the file. This is discussed in 6. I/O in Exiv2

I would like to express my dismay with the design of most image containers. There is a much simpler design used by macOS and that is a bundle. A bundle is a directory of files which includes the file Info.plist. It appears in the Finder to be a simple entity like a file. The terminal command ditto is provided to copy them. All programming languages can manipulte files. The metadata in an image should be a little Tiff or sidecar in a bundle. In principle, a container such as Tiff is a collection of streams that are both relocatable and never reference external data. Sadly, TIFF and JPEG make it very easy to break both rules. The design of JPEG makes it almost impossible to edit anything without relocating all the data. The situation with video is even more serious as the files are huge. In the PDF format, the file maintains a directory of objects. The objects can be safely relocated because objects reference each other by name and not the file offset.

There are tags in Tiff such as ImageWidth which cannot be modified without rewriting the pixels in the image. Exif protects those tags in the functions TiffHeader::isImageTag() and Cr2Header::isImageTag().

The Adobe Camera Raw Convertor installs CameraProfiles .dcp files in /Library/Application Support/Adobe/CameraRaw/CameraProfiles/ (on macOS). Camera Profiles are defined in the Adobe DNG Specification. They are a modified TIFF format which has the Signature “IIRClong”. Example:

569 rmills@rmillsmm-local:~/gnu/exiv2/team/book $ dmpf count=40 files/NikonD5300.dcp

0 0: IIRC.___._..._.___.___!.._.___._ -> 49 49 52 43 08 00 00 00 11 00 14 c6 02 00 0c 00 00 00 da 00 00 00 21 c6 0a 00 09 00 00 00 e6 00

0x20 32: __".._._ -> 00 00 22 c6 0a 00 09 00

570 rmills@rmillsmm-local:~/gnu/exiv2/team/book $ build/tvisitor files/NikonD5300.dcp

STRUCTURE OF TIFF FILE (II): files/NikonD5300.dcp

address | tag | type | count | offset | value

10 | 0xc614 Exif.DNG.UniqueCameraModel | ASCII | 12 | 218 | Nikon D5300

22 | 0xc621 Exif.DNG.ColorMatrix1 | SRATIONAL | 9 | 230 | 9672/10000 4294963143/10000 64/10000 +++

34 | 0xc622 Exif.DNG.ColorMatrix2 | SRATIONAL | 9 | 302 | 6988/10000 4294965912/10000 42949665 +++

46 | 0xc65a Exif.DNG.CalibrationIllumi.. | SHORT | 1 | | 17

58 | 0xc65b Exif.DNG.CalibrationIllumi.. | SHORT | 1 | | 21

70 | 0xc6f4 Exif.DNG.ProfileCalibratio.. | ASCII | 10 | 374 | com.adobe

82 | 0xc6f8 Exif.DNG.ProfileName | ASCII | 17 | 384 | Camera Landscape

94 | 0xc6fc Exif.DNG.ProfileToneCurve | FLOAT | 128 | 402 | 0 0 983631792 989550973 992020400 99 +++

106 | 0xc6fd Exif.DNG.ProfileEmbedPolicy | LONG | 1 | | 1

118 | 0xc6fe Exif.DNG.ProfileCopyright | ASCII | 35 | 914 | Copyright 2012 Adobe Systems, Inc.

130 | 0xc714 Exif.DNG.ForwardMatrix1 | SRATIONAL | 9 | 950 | 7978/10000 1352/10000 313/10000 2880 +++

142 | 0xc715 Exif.DNG.ForwardMatrix2 | SRATIONAL | 9 | 1022 | 7978/10000 1352/10000 313/10000 2880 +++

154 | 0xc725 Exif.DNG.ProfileLookTableD.. | LONG | 3 | 1094 | 90 16 16

166 | 0xc726 Exif.DNG.ProfileLookTableD.. | FLOAT | 69120 | 1106 | 0 1065353216 1065353216 1109273108 1 +++

178 | 0xc7a4 Exif.DNG.ProfileLookTableE.. | LONG | 1 | | 1

190 | 0xc7a5 Exif.DNG.BaselineExposureO.. | SRATIONAL | 1 | 277586 | 4294967261/100

202 | 0xc7a6 Exif.DNG.DefaultBlackRender | LONG | 1 | | 1

END: files/NikonD5300.dcp

571 rmills@rmillsmm-local:~/gnu/exiv2/team/book $

JPEG and EXF are almost the same thing, however most graphics applications will reject EXF because it is not a valid JPEG. ExifTool also supports EXF. In tvisitor.cpp, class JpegImage handles both and the only difference is respected in JpegImage::valid():

bool JpegImage::valid()

{

IoSave restore(io(),0);

bool result = false;

byte h[2];

io_.read(h,2);

if ( h[0] == 0xff && h[1] == 0xd8 ) { // .JPEG

start_ = 0;

format_ = "JPEG";

endian_ = keLittle;

result = true;

} else if ( h[0] == 0xff && h[1]==0x01 ) { // .EXV

DataBuf buf(5);

io_.read(buf);

if ( buf.is("Exiv2") ) {

start_ = 7;

format_ = "EXV";

endian_ = keLittle;

result = true;

}

}

return result;

} // JpegImage::valid()And here it is in action:

.../book/build $ ./tvisitor -pS ~/Stonehenge.jpg

STRUCTURE OF JPEG FILE (II): /Users/rmills/Stonehenge.jpg

address | tag type count | value

0 | 0xffd8 SOI

2 | 0xffe1 APP1 | 15288 | Exif__II*_.___._..._.___.___..._.___ +++

15292 | 0xffe1 APP1 | 2610 | http://ns.adobe.com/xap/1.0/_<?xpack +++

17904 | 0xffed APP13 | 96 | Photoshop 3.0_8BIM.._____'..__._...Z +++

18002 | 0xffe2 APP2 | 4094 | MPF_II*_.___.__.._.___0100..._.___._ +++

22098 | 0xffdb DQT | 132

22232 | 0xffc0 SOF0 | 17

22251 | 0xffc4 DHT | 418

22671 | 0xffda SOS

END: /Users/rmills/Stonehenge.jpg

.../book/build $ exiv2 -ea --verbose --force ~/Stonehenge.jpg

File 1/1: /Users/rmills/Stonehenge.jpg

Writing Exif data from /Users/rmills/Stonehenge.jpg to /Users/rmills/Stonehenge.exv

Writing IPTC data from /Users/rmills/Stonehenge.jpg to /Users/rmills/Stonehenge.exv

Writing XMP data from /Users/rmills/Stonehenge.jpg to /Users/rmills/Stonehenge.exv

.../book/build $ ./tvisitor -pS ~/Stonehenge.exv

STRUCTURE OF EXV FILE (II): /Users/rmills/Stonehenge.exv

address | tag type count | value

0 | 0xff01

7 | 0xffe1 APP1 | 15296 | Exif__II*_.___._..._.___.___..._.___ +++

15305 | 0xffe1 APP1 | 2610 | http://ns.adobe.com/xap/1.0/_<?xpack +++

17917 | 0xffed APP13 | 68 | Photoshop 3.0_8BIM.._____...__._...Z +++

17987 | 0xffd9 EOI

END: /Users/rmills/Stonehenge.exv

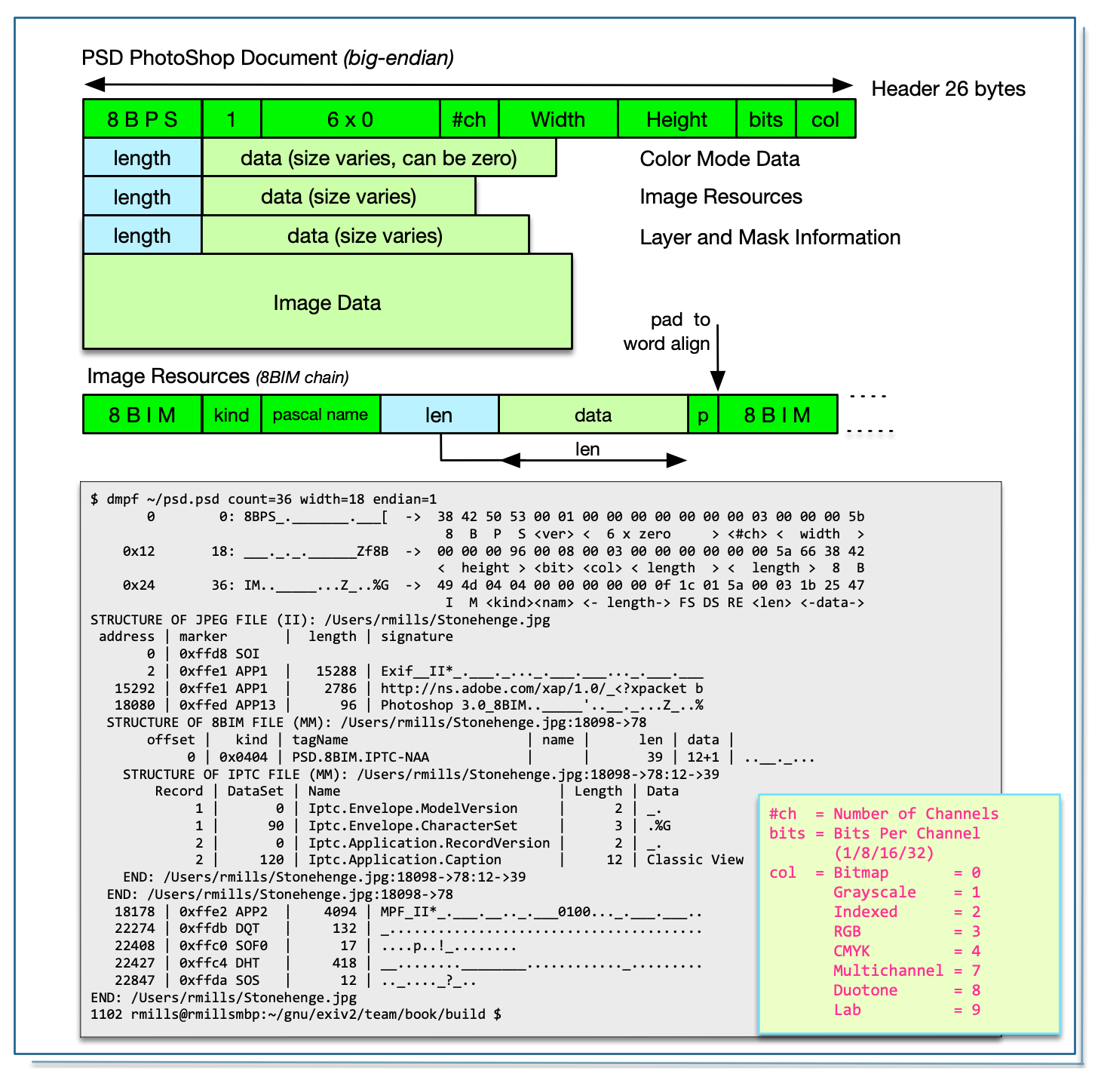

.../book/build $ This is an 8BIM chain and is explained in PSD PhotoShop Document

The JPEG standard restricts a single segment of a JPEG to 64k bytes because the length field is a 16 bit uint16_t. Exif, XMP and ICC frequently exceed 64k. Regrettably three different schemes are used to enable multiple consecutive segments to be coalesced into a larger block.

tvisitor.cpp supports Adobe and AGFA extended JPEG.

Adobe have created an ad-hoc standard by placing consecutive APP1 segments with the signature Exif\0\0. This ad-hoc standard is defined in Adobe’s XMP Specification Part 3 2016+.

Exiv2 has no code to deal with this. It can neither read nor write these files. In fact, JpegImage::writeMetadata() currently throws when asked to write more than 64k into a JPEG.

This is discussed here: https://dev.exiv2.org/issues/1232 and here is the output of the test files which were contributed by Phil Harvey.

.../book/build $ ./tvisitor -pS ~/cs4_extended_exif.jpg

STRUCTURE OF JPEG FILE (II): /Users/rmills/cs4_extended_exif.jpg

address | marker | length | signature

0 | 0xffd8 SOI

2 | 0xffe0 APP0 | 16 | JFIF_..._._.__..

20 | 0xffe1 APP1 | 65498 | Exif__MM_*___._..._.___.___n.._.___._.__

65520 | 0xffe1 APP1 | 65498 | Exif__g keys we require'd nex

131020 | 0xffe1 APP1 | 52820 | Exif__) if ($$segDataPt =~ /^

183842 | 0xffed APP13 | 4440 | Photoshop 3.0_8BIM..____....__.__..x..#-

188284 | 0xffe1 APP1 | 4323 | http://ns.adobe.com/xap/1.0/_<?xpacket b

192609 | 0xffe1 APP1 | 65477 | http://ns.adobe.com/xmp/extension/_C8400

258088 | 0xffe1 APP1 | 65477 | http://ns.adobe.com/xmp/extension/_C8400

323567 | 0xffe1 APP1 | 56466 | http://ns.adobe.com/xmp/extension/_C8400

380035 | 0xffe2 APP2 | 3160 | ICC_PROFILE_..__.HLino..__mntrRGB XYZ ..

383197 | 0xffee APP14 | 14 | Adobe_d.___...

383213 | 0xffdb DQT | 132 | _.......................................

383347 | 0xffc0 SOF0 | 17 | ..T...."_........

383366 | 0xffdd DRI | 4 | _...

383372 | 0xffc4 DHT | 319 | __........_______._..........._........_

383693 | 0xffda SOS | 12 | .._...._?_.T

END: /Users/rmills/cs4_extended_exif.jpg

.../book/build $ ./tvisitor -pS ~/multi-segment_exif.jpg

STRUCTURE OF JPEG FILE (II): /Users/rmills/multi-segment_exif.jpg

address | marker | length | signature

0 | 0xffd8 SOI

2 | 0xffe1 APP1 | 65535 | Exif__II*_.___._..._.___.___..._.___.___

65539 | 0xffe1 APP1 | 5603 | Exif__..................................

71144 | 0xffdb DQT | 132 | _.......................................

71278 | 0xffc4 DHT | 418 | __........________............_.........

71698 | 0xffc0 SOF0 | 17 | ..0.@..!_........

71717 | 0xffda SOS | 12 | .._...._?_..

END: /Users/rmills/multi-segment_exif.jpg

.../book/build $ This is discussed in https://dev.exiv2.org/issues/1232 I think it is desirable to support reading this data. Exiv2 should write using Adobe’s JPEG > 64k ad-hoc standard.

.../book/build $ ./tvisitor -pS ~/Agfa.jpg

STRUCTURE OF JPEG FILE (II): /Users/rmills/Agfa.jpg

address | marker | length | signature

0 | 0xffd8 SOI

2 | 0xffe1 APP1 | 46459 | Exif__II*_.___._..._.___.___..._.___.___..._._

46463 | 0xffe3 APP3 | 65535 | ...._._.......................................

112000 | 0xffe4 APP4 | 65535 | ..Hc..w .8<...z..M.77.h...{......C.y1...... .k

177537 | 0xffe5 APP5 | 7243 | .U......K..u=).pl.W.F...B.$.3....mg}q.....Hb.m

184782 | 0xffdb DQT | 132 |

184916 | 0xffc0 SOF0 | 17 |

184935 | 0xffc4 DHT | 75 |

185012 | 0xffda SOS | 12 |

END: /Users/rmills/Agfa.jpg

.../book/build $ The Agfa MakerNote contains an IFD which is preceded by ABC_II#E where #E is number of entries in the IFD. This is discussed in 2.5 MakerNotes

This is documented by ICC in ICC1v43_2010-12.pdf and implemented in Exiv2 for both reading and writing. The ICC profile has a signature of ICC_PROFILE_ followed by two uint8_t values which are the chunk sequence and the chunks count. The remainder of the data is the ICC profile. The test file test/data/ReaganLargeJpg.jpg has data in the format.

1155 rmills@rmillsmbp:~/gnu/github/exiv2/0.27-maintenance $ exiv2 -pS test/data/ReaganLargeJpg.jpg

STRUCTURE OF JPEG FILE: test/data/ReaganLargeJpg.jpg

address | marker | length | data

0 | 0xffd8 SOI

2 | 0xffe0 APP0 | 16 | JFIF.....,.,....

20 | 0xffe1 APP1 | 4073 | Exif..MM.*......................

4095 | 0xffe1 APP1 | 6191 | http://ns.adobe.com/xap/1.0/.<?x

10288 | 0xffe2 APP2 | 65535 | ICC_PROFILE...... APPL....prtrRG chunk 1/25

75825 | 0xffe2 APP2 | 65535 | ICC_PROFILE....S...r.R...t.RT..w chunk 2/25

141362 | 0xffe2 APP2 | 65535 | ICC_PROFILE.....o..b.tn..Q.Km... chunk 3/25

...

1517639 | 0xffe2 APP2 | 65535 | ICC_PROFILE...9.0.894.0.901.0.90 chunk 24/25

1583176 | 0xffe2 APP2 | 41160 | ICC_PROFILE....463.0.465.0.469.0 chunk 25/25

1624338 | 0xffdb DQT | 67

1624407 | 0xffdb DQT | 67

1624476 | 0xffc2 SOF2 | 17

1624495 | 0xffc4 DHT | 30

1624527 | 0xffc4 DHT | 27

1624556 | 0xffda SOS

1156 rmills@rmillsmbp:~/gnu/github/exiv2/0.27-maintenance $ This is documented by Adobe in the XMP Specification 2016+ and implemented in Exiv2 in the API JpegBase::printStructure::(kpsXMP). It is not implemented in JpegBase::readMetadata().

Adobe have implemented transparency in JPEG by storing a PostScript clippath in the APP13 Photoshop 3.0 segment. Exiv2 has no code to deal with this. There is an Exif tag ClipPath which Exiv2 does support. I have encountered PhotoShop APP13 transparency. I’ve never encountered Exif.Image.ClipPath.

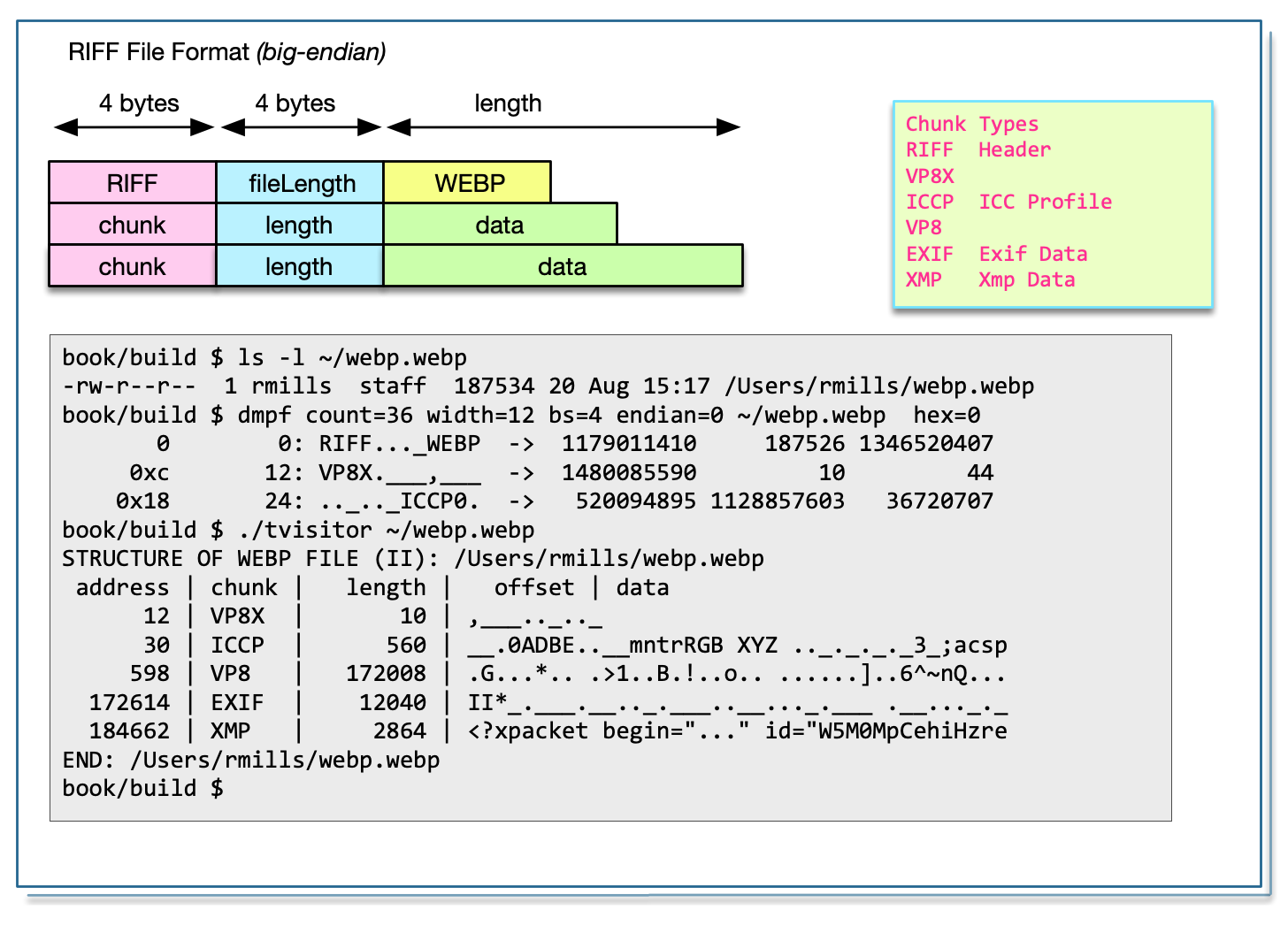

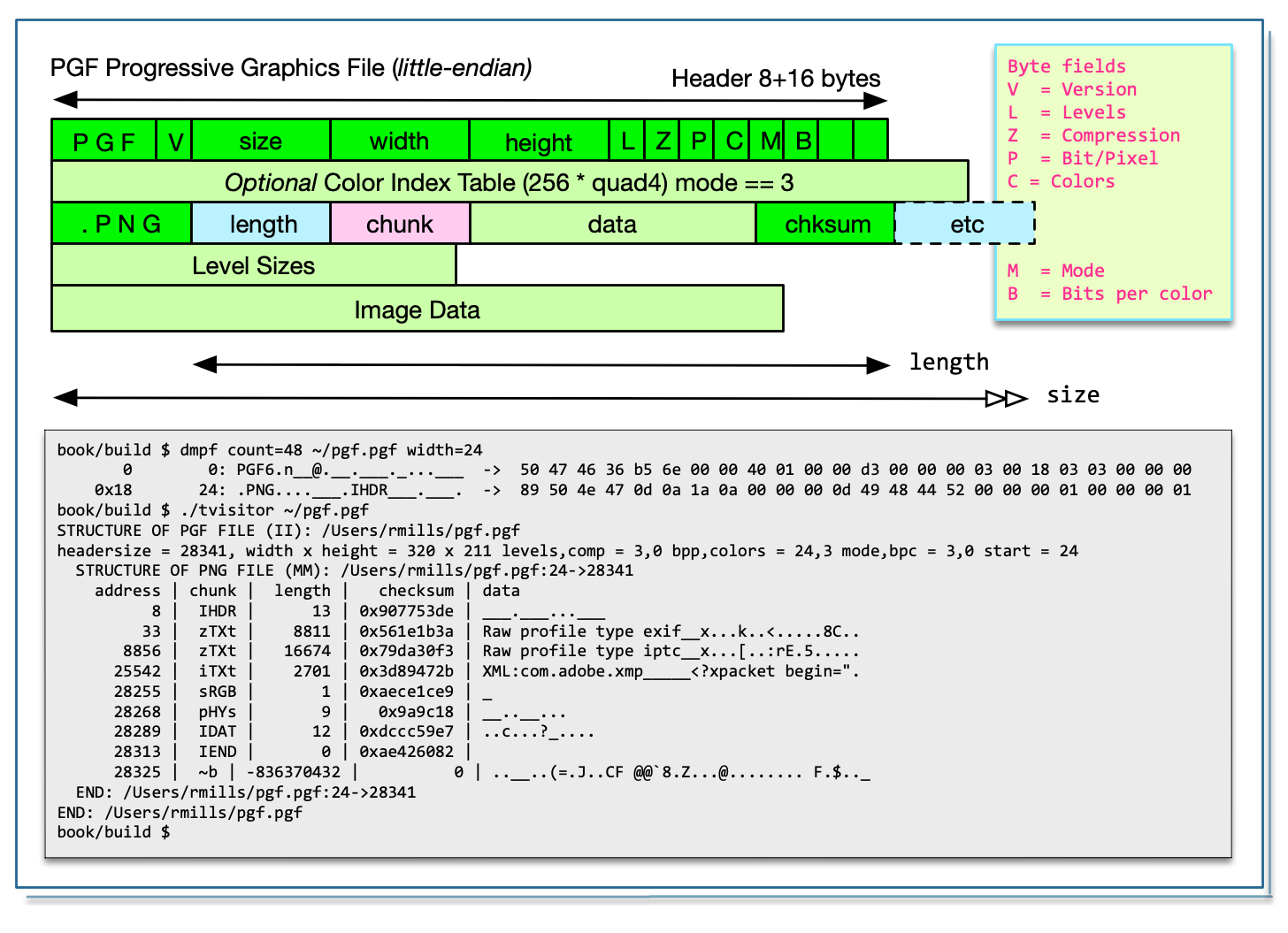

The PNG specification is available https://www.w3.org/TR/2003/REC-PNG-20031110/.

PNG is always bigEndian encoded. PNG has an 8 byte fixed header followed by a linked list of chunks. A chunk is 12 or more bytes and has a uint32_t length, char[4] chunk identifier, followed by binary data. The chunk data is trailed by a uint32_t checksum calculated by the zlib compression library.

We validate a PNG with the following code:

bool PngImage::valid()

{

IoSave restore(io(),0);

bool result = true ;

const byte pngHeader[] = { 0x89, 0x50, 0x4E, 0x47, 0x0D, 0x0A, 0x1A, 0x0A };

for ( size_t i = 0 ; result && i < sizeof (pngHeader ); i ++) {

result = io().getb() == pngHeader[i];

}

if ( result ) {

start_ = 8 ;

endian_ = keBig ;

format_ = "PNG" ;

}

return result;

}Navigating a PNG is straight forward:

void PngImage::accept(class Visitor& v)

{

if ( valid() ) {

v.visitBegin(*this);

IoSave restore(io(),start_);

uint64_t address = start_ ;

while ( address < io().size() ) {

io().seek(address );

uint32_t length = io().getLong(endian_);

uint64_t next = address + length + 12;

char chunk [5] ;

io().read(chunk ,4) ;

chunk[4] = 0 ; // nul byte

io().seek(next-4); // jump over data to checksum

uint32_t chksum = io().getLong(endian_);

v.visitChunk(io(),*this,address,chunk,length,chksum); // tell the visitor

address = next ;

}

v.visitEnd(*this);

}

}Reporting Exif and XMP is also easy.

void Visitor::visitChunk(Io& io,Image& image

,uint64_t address,char* chunk,uint32_t length,uint32_t chksum)

{

IoSave save(io,address+8);

DataBuf data(length);

io.read(data);

if ( option() & (kpsBasic | kpsRecursive) ) {

out() << stringFormat(" %8d | %s | %7d | %#10x | ",address,chunk,length,chksum);

if ( length > 40 ) length = 40;

out() << data.toString(kttUndefined,length,image.endian()) << std::endl;

}

if ( option() & kpsRecursive && std::strcmp(chunk,"eXIf") == 0 ) {

Io tiff(io,address+8,length);

TiffImage(tiff).accept(*this);

}

if ( option() & kpsXMP && std::strcmp(chunk,"iTXt")==0 ) {

if ( data.strcmp("XML:com.adobe.xmp")==0 ) {

out() << data.pData_+22 ;

}

}

}As PNG chunks have a 32 bit length field, they can be stored as a single chunk. We don’t need the messy arrangements used in JPEG to distribute data into multiple segments of less than 64k. XMP is normally stored as a iTXt/uncompressed or zTXt/compressed block. The signature at the start of the chunk is never compressed.

When an ICC profile is required, it is stored as an iCCP chunk. The signature is “ICC Profile”. The profile is always compressed.

1174 rmills@rmillsmbp:~/gnu/github/exiv2/0.27-maintenance $ exiv2 -pS test/data/ReaganLargePng.png

STRUCTURE OF PNG FILE: test/data/ReaganLargePng.png

address | chunk | length | data | checksum

8 | IHDR | 13 | ............ | 0x8cf910c3

33 | zTXt | 8461 | Raw profile type exif..x...iv. | 0x91fbf6a0

8506 | zTXt | 636 | Raw profile type iptc..x..TKn. | 0x4e5178d3

9154 | iTXt | 7156 | XML:com.adobe.xmp.....<?xpacke | 0x8d6d70ba

16322 | gAMA | 4 | .... | 0x0bfc6105

16338 | iCCP | 1151535 | ICC profile__x...UP.........!! | 0x11f49e31

1167885 | bKGD | 6 | ...... | 0xa0bda793

1167903 | pHYs | 9 | ...#...#. | 0x78a53f76

1167924 | tIME | 7 | ......2 | 0x582d32e4

1167943 | zTXt | 278 | Comment..x.}..n.@....O..5..h.. | 0xdb1dfff5

1168233 | IDAT | 8192 | x...k.%.u%....D......GWW...ER. | 0x929ed75c

1176437 | IDAT | 8192 | .F('.T)\....D"]..."2 '(...D%.. | 0x52c572c0

1184641 | IDAT | 8192 | y-.....>....3..p.....$....E.Bj | 0x65a90ffb

1192845 | IDAT | 8192 | ....S....?..G.....G........... | 0xf44da161

1201049 | IDAT | 7173 | .evl...3K..j.S.....x......Z .D | 0xbe6d3574

1208234 | IEND | 0 | | 0xae426082

1175 rmills@rmillsmbp:~/gnu/github/exiv2/0.27-maintenance $ Some PNG chunks are flate compressed (lossless). You can build tvisitor.cpp with/without the Zlib compression flag using the cmake option -DEXIV2_ENABLE_PNG. This becomes the compiler define HAVE_LIBZ which enables additional code.

I’m very pleased to say that neither the Exiv2 or XMP metadata in the image book/png.png have been compressed and can be easily reported by tvisitor.cpp. It’s very satisfying to use images from this book as test data for the code in this book.

Several chunks are always compressed. For example, zTXt and iCCP. The payload of zTXt normally comprises a nul-terminated signature, a one byte compression flag (always zero) followed by compressed data. For example:

address | chunk | length | checksum | data | decompressed

16338 | iCCP | 1151535 | 0x11f49e31 | ICC profile__x...UP......._.!!B....a.qwW | _.. APPL..__prtrRGB Lab .._._._._._)acsp

<signature>__compressed data = decompressedThe flate compressed ICC profile follows the “ICC Profile__” signature.

The signatures: “Raw profile type iptc” and “Raw profile type exif” introduce a compressed block which when expanded is an ascii string with the following format. The number is count of hex code bytes. This is redundant and does not need to be decoded.

\n

exif\n

number\n

hexEncodedBinary\n

....This data is revealed by tvisitor as follows:

addr | chunk | length | checksum | data | decompressed | dehexed

33 | zTXt | 8461 | 0x91fbf6a0 | Raw profile type exif__x...iv. | .exif. 8414.457869660000 | Exif__II*_.___._._

8506 | zTXt | 636 | 0x4e5178d3 | Raw profile type iptc__x..TKn. | .iptc. 778.3842494d0404 | 8BIM..____....Z_..%G.Converting hex encoded binary is straight-forward. Because hex encoded binary is always longer than the data, decoding updates the input buffer and returns the updated length.

static int hexToString(char buff[],int length)

{

int r = 0 ; // resulting length

int t = 0 ; // temporary

bool first = true;

bool valid[256];

int value[256];

for ( int i = 0 ; i < 256 ; i++ ) valid[i] = false;

for ( int i = '0' ; i <= '9' ; i++ ) {

valid[i] = true;

value[i] = i - '0';

}

for ( int i = 'a' ; i <= 'f' ; i++ ) {

valid[i] = true;

value[i] = 10 + i - 'a';

}

for ( int i = 'A' ; i <= 'F' ; i++ ) {

valid[i] = true;

value[i] = 10 + i - 'A';

}

for (int i = 0; i < length ; i++ )

{

char x = buff[i];

if ( valid[x] ) {

if ( first ) {

t = value[x] << 4;

first = false ;

} else {

first = true;

buff[r++] = t + value[x];

}

}

}

return r;

}Here is an important section of the PNG standard concerning textual metadata:

11.3.4 Textual information

11.3.4.1 Introduction

PNG provides the tEXt, iTXt, and zTXt chunks for storing text strings associated with the image, such as an image description or copyright notice. Keywords are used to indicate what each text string represents. Any number of such text chunks may appear, and more than one with the same keyword is permitted.

11.3.4.2 Keywords and text strings

The following keywords are predefined and should be used where appropriate.

| Title | Short (one line) title or caption for image |

|---|---|

| Author | Name of image’s creator |

| Description | Description of image (possibly long) |

| Copyright | Copyright notice |

| Creation Time | Time of original image creation |

| Software | Software used to create the image |

| Disclaimer | Legal disclaimer |

| Warning | Warning of nature of content |

| Source | Device used to create the image |

| Comment | Miscellaneous comment |

Other keywords may be defined for other purposes. Keywords of general interest can be registered with the PNG Registration Authority. It is also permitted to use private unregistered keywords.

You can set Textual Information in PNG files using the ImageMagick utility mogrify.

868 rmills@rmillsmm-local:~/gnu/exiv2/team/book $ tvisitor exif.png | grep -e comment -e info -e source

869 rmills@rmillsmm-local:~/gnu/exiv2/team/book $ mogrify -set info 'I am info' exif.png

870 rmills@rmillsmm-local:~/gnu/exiv2/team/book $ mogrify -set source 'Source you know' exif.png

871 rmills@rmillsmm-local:~/gnu/exiv2/team/book $ mogrify -set comment 'Comment in a PNG' exif.png

872 rmills@rmillsmm-local:~/gnu/exiv2/team/book $ tvisitor exif.png | grep -e comment -e info -e source

127957 | tEXt | 24 | 0x1adeaee2 | comment_Comment in a PNG

128091 | tEXt | 14 | 0xd064ad9e | info_I am info

128117 | tEXt | 22 | 0xb1645ed2 | source_Source you know

873 rmills@rmillsmm-local:~/gnu/exiv2/team/book $ As tvisitor displays the chunks, no further processing is necessary to see this data for tEXt chunks.

Exiv2 does not provide support for PNG Textual Information. The subject is discussed here: https://github.com/Exiv2/exiv2/issues/1343. To support PNG Textual Information in Exiv2 requires a new “Family” of metadata with keys such as: Png.zTXt.Author. Adding a new “Family” is a considerable undertaking. The project to have a “unified” metadata container should be undertaken first.

There’s an option $ exiv2 -c abcdefg foo.jpg which will set the “Comment” in a JPEG file. You can print the comment with $ exiv2 -pc foo. A “Comment” in a JPEG is a top level COM segment in the JPEG. Somebody decided to use those commands on a PNG to update an iTXt chunk with the signature “Description”. I think that was a poor decision which has gone unnoticed.

Encoding of iTXt comments in PNG is perverse and implemented in the Exiv2 function tEXtToDataBuf() which is not in tvisitor.cpp

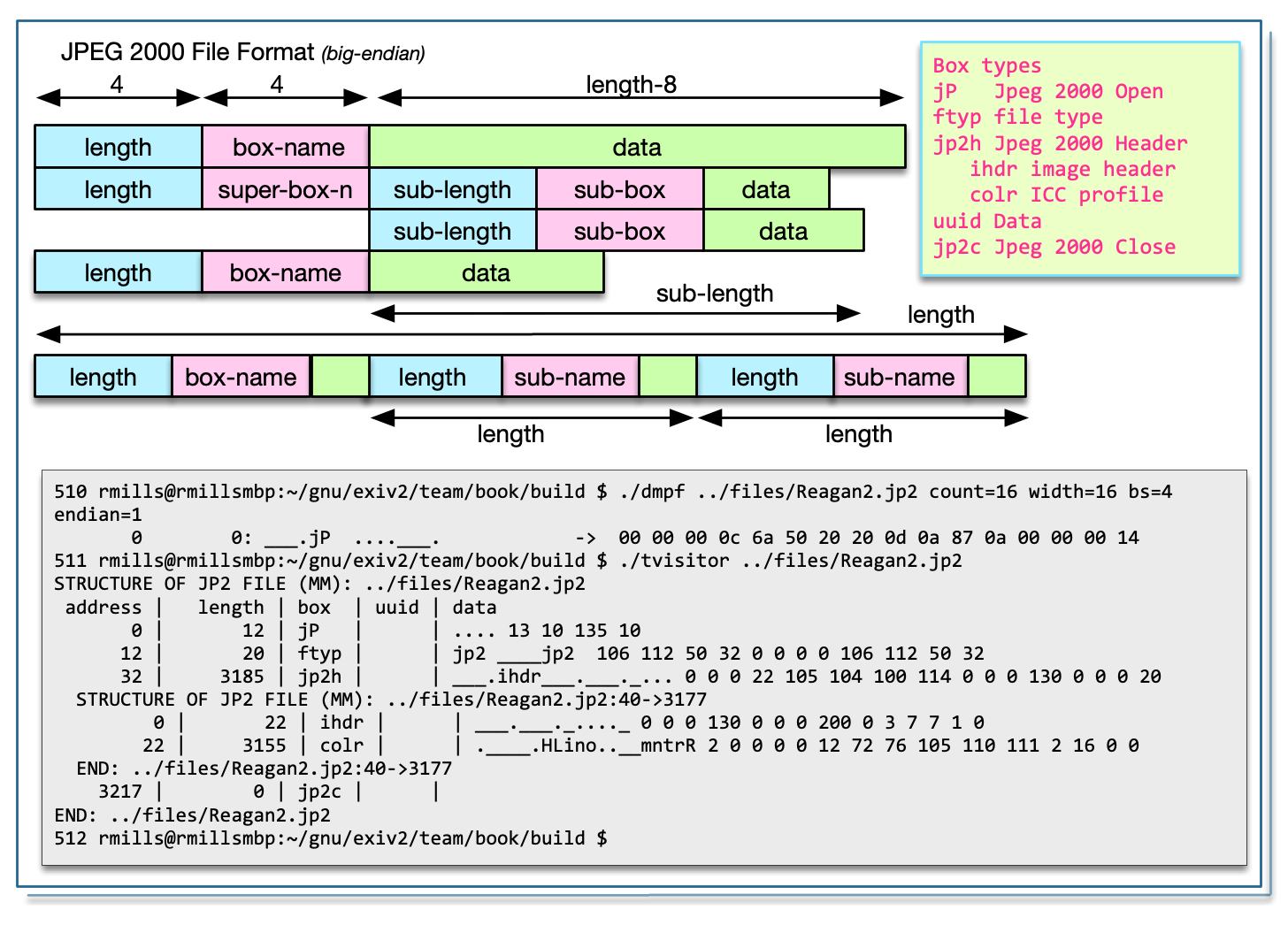

JPEG 2000 is defined in the standard: ISO/IEC 15444-1:2019 which is available here: https://www.iso.org/standard/78321.html

The JPEG 2000 file is a big-endian encoded BMFF Container. It consists of a linked lists of “boxes” which have a uint32_t length, char[4] box-type and (length-8) bytes of data. A box may be a “super-box” which is a container for other boxes. A “super-box” can have binary data before the box-chain. Reading the file is very easy, however you need the specification to decode the contents of a box.

I believe the “box” idea in BMFF is intended to address the issue I discussed about TIFF files. In order to rewrite an image, it is necessary for the data to be self contained and relocatable. Every “box” should be self contained with no offsets outside the box. My study of JP2 is restricted to finding the Exiv2, ICC, IPTC and XMP data. For sure these are self-contained blocks of binary data. The metadata boxes are of type uuid and begin with a 128bit/16 byte UUID to identify the data.

In a JP2 the first box, must be box-type of “jP__” and have a length of 12. The chain is terminated with a box-type of “jpcl”. Usually the terminal block will bring you to the end-of-file, however this should not be assumed as there can be garbage following the box-chain. The box-chain of a super-box is normally terminated by reaching the end of its data.

Validating a JP2 file is straight forward:

bool Jp2Image::valid()

{

if ( !valid_ ) {

start_ = 0;

IoSave restore (io(),start_);

uint32_t length = io().getLong(endian_);

uint32_t box ;

io().read(&box,4);

valid_ = length == 12 && boxName(box) == kJp2Box_jP;

}

return valid_ ;

}The accept function is also straight forward:

void Jp2Image::accept(class Visitor& v)

{

if ( valid() ) {

v.visitBegin(*this);

IoSave restore(io(),start_);

uint64_t address = start_ ;

while ( address < io().size() ) {

io().seek(address );

uint32_t length = io().getLong(endian_);

uint32_t box ;

io().read(&box,4);

v.visitBox(io(),*this,address,box,length); // tell the visitor

// recursion if superbox

if ( superBox(box) ) {

uint64_t subA = io().tell() ;

Jp2Image jp2(io(),subA,length-8);

jp2.valid_ = true ;

jp2.accept(v);

}

address = boxName(box) == kJp2Box_jp2c ? io().size() : address + length ;

}

v.visitEnd(*this);

}

}There is a little complication when you create the recursive Jp2Image. We do not wish to validate this because it never starts with box-type of “jP__”. We know the file is valid, so we set the valid_ flag before the recursion.

The function ReportVisitor::visitBox() is also straight forward:

void ReportVisitor::visitBox(Io& io,Image& image,uint64_t address

,uint32_t box,uint32_t length)

{

IoSave save(io,address+8);

length -= 8 ;

DataBuf data(length);

io.read(data);

std::string name = image.boxName (box);

std::string uuid = image.uuidName(data);

if ( option() & (kpsBasic | kpsRecursive) ) {

out() << indent() << stringFormat("%8d | %7d | %#10x %4s | %s | ",address,length,box,name.c_str(),uuid.c_str() );

if ( length > 40 ) length = 40;

out() << data.toString(kttUndefined,length,image.endian()) << std::endl;

}

if ( option() & kpsRecursive && uuid == "exif" ) {

Io tiff(io,address+8+16,data.size_-16); // uuid is 16 bytes (128 bits)

TiffImage(tiff).accept(*this);

}

if ( option() & kpsXMP && uuid == "xmp " ) {

out() << data.pData_+17 ;

}

}Although the JP2 file is big endian, the embedded Exif metadata may be little-endian encoded. That’s the case with test file Reagan.jp2.

.../book/build $ ./tvisitor -pR ../test/data/Reagan.jp2

STRUCTURE OF JP2 FILE (MM): ../test/data/Reagan.jp2

address | length | box | uuid | data

0 | 4 | 0x2020506a jP | | ....

12 | 12 | 0x70797466 ftyp | | jp2 ____jp2

32 | 37 | 0x6832706a jp2h | | ___.ihdr___.___._..._____.colr._____.

STRUCTURE OF JP2 FILE (MM): ../test/data/Reagan.jp2:40->37

address | length | box | uuid | data

0 | 14 | 0x72646869 ihdr | | ___.___._...__

22 | 7 | 0x726c6f63 colr | | ._____.

END: ../test/data/Reagan.jp2:40->37

77 | 1334 | 0x64697575 uuid | exif | JpgTiffExif->JP2II*_.___._..._..__.___..

STRUCTURE OF TIFF FILE (II): ../test/data/Reagan.jp2:101->1318

address | tag | type | count | offset | value

10 | 0x010e Exif.Image.ImageDescription | ASCII | 403 | 170 | 040621-N-6536T-062

22 | 0x010f Exif.Image.Make | ASCII | 18 | 574 | NIKON CORPORATION

...

142 | 0x8769 Exif.Image.ExifTag | LONG | 1 | | 2191130661

STRUCTURE OF TIFF FILE (II): ../test/data/Reagan.jp2:101->1318

address | tag | type | count | offset | value

714 | 0x829a Exif.Photo.ExposureTime | RATIONAL | 1 | 1162 | 1/125

...

1122 | 0xa40a Exif.Photo.Sharpness | SHORT | 1 | | 0

END: ../test/data/Reagan.jp2:101->1318

STRUCTURE OF TIFF FILE (II): ../test/data/Reagan.jp2:101->1318

address | tag | type | count | offset | value

1302 | 000000 Exif.GPSInfo.GPSVersionID | UBYTE | 4 | | 122 97 98 101

END: ../test/data/Reagan.jp2:101->1318

END: ../test/data/Reagan.jp2:101->1318

1419 | 934 | 0x64697575 uuid | iptc | 3.....G#.......8..__._...._.040621-N-653

2361 | 5582 | 0x64697575 uuid | xmp | .z....B..q......<?xpacket begin="..." id

7951 | 32650 | 0x6332706a jp2c | | .O.Q_/_____.___.___________.___.________

END: ../test/data/Reagan.jp2

.../book/build $ These are stored in the ‘colr’ box which is a sub-box of ‘jp2h’. I have found the specification very unsatisfactory. ISO/IEC 15444-2 discusses ColourInformationBox extends Box(‘colr’). I haven’t found the definition of ‘colr’. I enquired on the ExifTool Forum and Phil offered advice which has been implemented in jp2image.cpp. There are two ways to encode the profile. You can use a uuid box with the uuid of “\x01\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x10\x00\x00\x05\x1c”. The box payload is the ICC profile. Or you can use the ‘colr’ box which has 3 padding bytes “\02\0\0” followed by the ICC profile. So the length of the box will be 8 (the box) +3 (padding) +iccProfile.size()

I found an older version of the spec in which ‘colr’ is documented on p161. http://hosting.astro.cornell.edu/~carcich/LRO/jp2/ISO_JPEG200_Standard/INCITS+ISO+IEC+15444-1-2000.pdf

.../book/build $ ./tvisitor ~/gnu/github/exiv2/0.27-maintenance/test/data/Reagan2.jp2

STRUCTURE OF JP2 FILE (MM): /Users/rmills/gnu/github/exiv2/0.27-maintenance/test/data/Reagan2.jp2

address | length | box | uuid | data

0 | 4 | 0x2020506a jP | | ....

12 | 12 | 0x70797466 ftyp | | jp2 ____jp2

32 | 3177 | 0x6832706a jp2h | | ___.ihdr___.___._....___.Scolr.____.HLin

STRUCTURE OF JP2 FILE (MM): /Users/rmills/gnu/github/exiv2/0.27-maintenance/test/data/Reagan2.jp2:40->3177

address | length | box | uuid | data

0 | 14 | 0x72646869 ihdr | | ___.___._...._

22 | 3147 | 0x726c6f63 colr | | .____.HLino..__mntrRGB XYZ .._._._._1__a

END: /Users/rmills/gnu/github/exiv2/0.27-maintenance/test/data/Reagan2.jp2:40->3177

3217 | -8 | 0x6332706a jp2c | | .O.Q_/_____.___.___________.___.________

END: /Users/rmills/gnu/github/exiv2/0.27-maintenance/test/data/Reagan2.jp2

.../book/build $ As you can see, the ‘colr’ box is stored at 40+22 bytes into the file and has a length of 3147. The first four bytes of an ICC profile is the length of the file which in this case is 3144 bytes. The next 4 bytes of the profile are the maker and in this case is Linotype.

.../book/build $ dmpf skip=$((40+22)) count=19 endian=1 ~/gnu/github/exiv2/0.27-maintenance/test/data/Reagan2.jp2

0x3e 62: __.Scolr.____.HLino -> 00 00 0c 53 63 6f 6c 72 02 00 00 00 00 0c 48 4c 69 6e 6f 02

<--3147---> c o l r <-pad--> <--3144---> L i n o

.../book/build $I obtained the standard here: https://mpeg.chiariglione.org/standards/mpeg-4/iso-base-media-file-format/text-isoiec-14496-12-5th-edition

There has been a lot of discussion in Team Exiv2 concerning the legality of reading this file. I don’t believe it’s illegal to read metadata from a container. I believe it’s illegal to decode proprietary encoded data stored in the image. However the metadata is not protected in anyway. So, I have implemented this in tvisitor.cpp. The code in Exiv2 src/bmffimage.cpp is derived from the class J2Image code in this book.

The most obvious difference between JP2000 and BMFF is the first box. For JP2, this is of type jP (jPspacespace) followed by ftyp. BMFF files begin with an ftyp box. The syntax of the ftyp box is:

class FileTypeBox extends Box(‘ftyp’) {

unsigned int(32) major_brand;

unsigned int(32) minor_version;

unsigned int(32) compatible_brands[]; // to end of the box

}So there are two uint32_t values which are the brand and minor_version. Then zero or more uint32_t values for compatible brands.

A box name is a 4 byte big-endian byte stream and stored in a uint32_t. It is not nul-terminated. So the box type jP (jPspacespace) is 0x2020506a, and ftyp is 0x70797666.

This is mechanism to store binary data in any format. The BMFF Specification states: Type Fields not defined here are reserved. Private extensions shall be achieved through the ‘uuid’ type. The uuid box has a 128 bit (16 byte) UUID to identify the data, followed by the data. This is similar to the “signature” in JPEG segment or PNG chunk.

I’ve found the open-source product ISOBMFF Explorer very useful in learning about this file format. https://imazing.com/isobmff/download. The code is available from: https://github.com/DigiDNA/ISOBMFF.

I built it as follows. You should use the git –recursive option to ensure that Submodules are also cloned.

$ git clone --recursive https://github.com/DigiDNA/ISOBMFF --depth 1

$ open ISOBMFF.xcodeproj/Very nice program with very nice code. In addition to the GUI/Explorer, a command-line application ISOBMFF-Dump is provided. I also built it with Visual Studio 2019. I believe the GUI is only provided on the Mac. The command-line application is supported on Mac, Windows and Linux.

It did not build out of the box for me on Ubuntu18.04. [https://github.com/DigiDNA/ISOBMFF/issues/12](https://github.com/DigiDNA/ISOBMFF/issues/12}

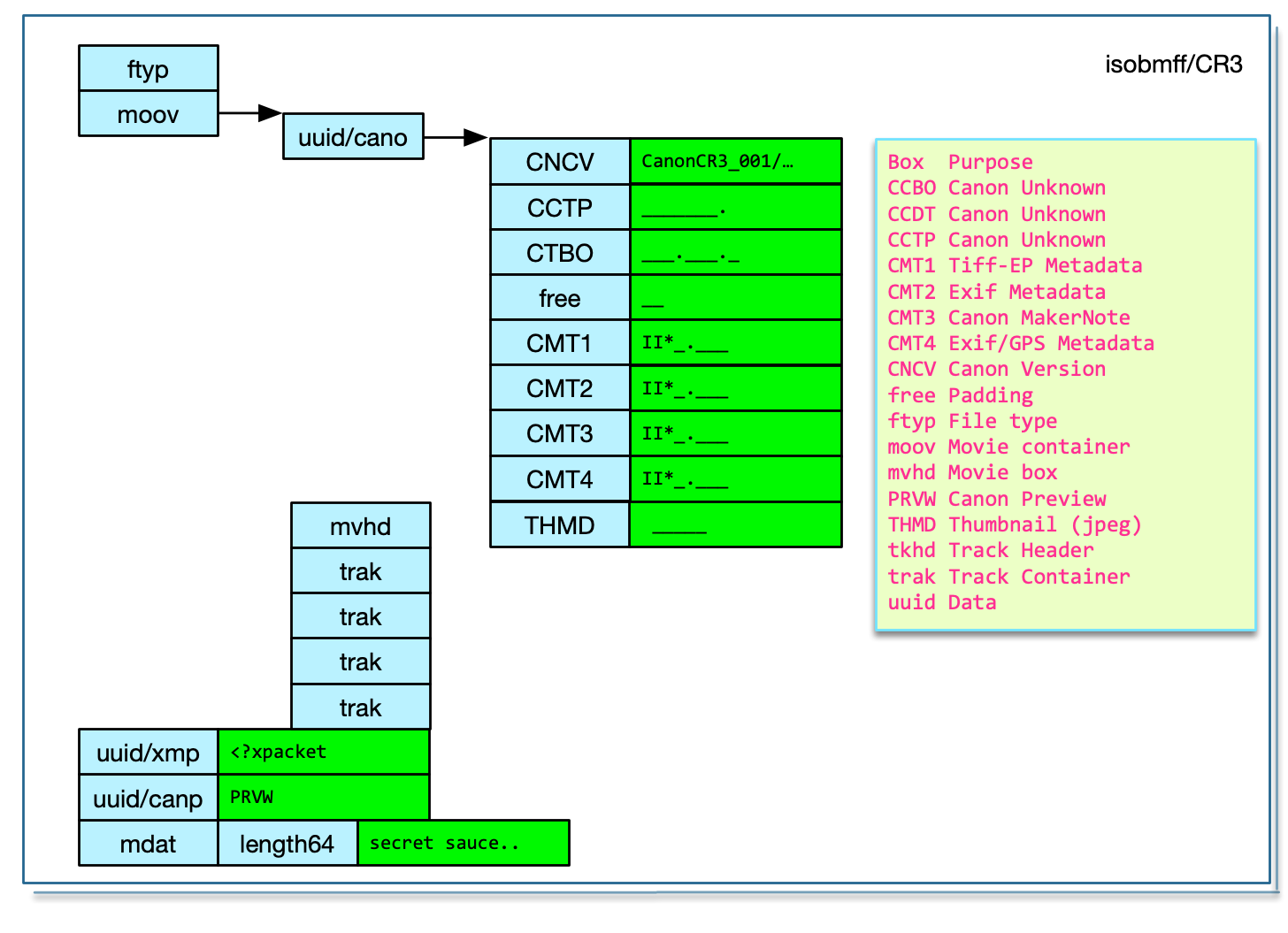

This is a dump from a CR3:

$ tvisitor ~/cr3.cr3

STRUCTURE OF CR3 FILE (MM): /Users/rmills/cr3.cr3

address | length | box | uuid | data

0 | 16 | 0x70797466 ftyp | | crx ___.crx isom

24 | 22784 | 0x766f6f6d moov | | __PXuuid............F+jH___&CNCVCanonCR3

STRUCTURE OF JP2 FILE (MM): /Users/rmills/cr3.cr3:32->22784

0 | 20560 | 0x64697575 uuid | can1 | ___&CNCVCanonCR3_001/00.09.00/00.00.00__

STRUCTURE OF JP2 FILE (MM): /Users/rmills/cr3.cr3:32->22784:24->20552

0 | 30 | 0x56434e43 CNCV | | CanonCR3_001/00.09.00/00.00.00

38 | 84 | 0x50544343 CCTP | | _______.___.___.CCDT_______._______.___.

130 | 84 | 0x4f425443 CTBO | | ___.___.______Y _____._.___._____.Y8____

222 | 2 | 0x65657266 free | | __

232 | 384 | 0x31544d43 CMT1 | | II*_.___.__.._.___p.__..._.___..__..._._

624 | 1056 | 0x32544d43 CMT2 | | II*_.___._..._.___..__..._.___..__".._._

1688 | 5168 | 0x33544d43 CMT3 | | II*_.___/_._._1___B.__._._.___..__._._._

6864 | 1808 | 0x34544d43 CMT4 | | II*_.___.___._.___..____________________

8680 | 11856 | 0x424d4854 THMB | | _____._x__.=_.__...._._.................

20544 | 100 | 0x6468766d mvhd | | ____..4...4.___.___._.__.____________.__

END: /Users/rmills/cr3.cr3:32->22784:24->20552

20568 | 100 | 0x6468766d mvhd | | ____..4...4.___.___._.__.____________.__

20676 | 476 | 0x6b617274 trak | | ___\tkhd___...4...4.___._______.________

21160 | 576 | 0x6b617274 trak | | ___\tkhd___...4...4.___._______.________

21744 | 592 | 0x6b617274 trak | | ___\tkhd___...4...4.___._______.________

22344 | 432 | 0x6b617274 trak | | ___\tkhd___...4...4.___._______.________

END: /Users/rmills/cr3.cr3:32->22784

22816 | 65552 | 0x64697575 uuid | xmp | <?xpacket begin='...' id='W5M0MpCehiHzre..'

88376 | 264921 | 0x64697575 uuid | can2 | _______._...PRVW_____..T.8_._......._._.

353305 | -7 | 0x7461646d mdat | | _____.j....._._.........................

END: /Users/rmills/cr3.cr3The CR3 format has been well documented by Laurent Clévy here: https://github.com/lclevy/canon_cr3.git

The XMP is clearly marked in a uuid packet. The Exif metadata is stored as 4 embedded TIFF files in the Canon uuid packet. The four files are the ‘tiffTags’, ‘exifTags’, ‘canonTags’ and ‘gpsTags’. In the test files, the gpsTags are about 1800 bytes of mostly zeros!

Laurent hasn’t identified IPTC and ICC data. There is a discussion about concerning ICC in JP2000 files and I believe that’s what is used by CR3. I have not discovered anything about IPTC in CR3 files.

The THMB record is a JPEG and written at an offset of 24 bytes into the record.

$ (dd bs=1 skip=32 count=22784 if=~/cr3.cr3 | dd bs=1 skip=24 count=20552 | dd bs=1 skip=$((8680+24)) count=$((11856-24)) | exiv2 -pS -) 2>/dev/null

STRUCTURE OF JPEG FILE: 1596571254.exiv2_temp

address | marker | length | data

0 | 0xffd8 SOI

2 | 0xffdb DQT | 132

136 | 0xffc0 SOF0 | 17

155 | 0xffc4 DHT | 418

575 | 0xffda SOS In this case, the thumbnail is 160x120 pixels. 11837 is the filesize.

$ (dd bs=1 skip=32 count=22784 if=~/cr3.cr3 | dd bs=1 skip=24 count=20552 | dd bs=1 skip=8680 count=24 | dmpf -endian=1 -bs=2 hex=0 -) 2>/dev/null

0 0: __.XTHMB_____._x__.=_.__ -> 0 11864 21576 19778 0 0 160 120 0 11837 1 0

$ ls -l foo.jpg

-rw-r--r--@ 1 rmills staff 11832 4 Aug 20:58 foo.jpgLaurent has documented this as: THMB (Thumbnail) from uuid = 85c0b687-820f-11e0-8111-f4ce462b6a48

| Offset | type | size | content |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | long | 1 | size of this tag |

| 4 | char | 4 | “THMB” |

| 8 | byte | 1 | likely version, value=0 or 1 |

| 9 | bytes | 3 | likely flags, value = 0 |

for version 0:

| Offset | type | size | content |

|---|---|---|---|

| 12/0xc | short | 1 | width (160) |

| 14/0xe | short | 1 | height (120) |

| 16/0x10 | long | 1 | jpeg image size (jpeg_size) |

| 20/0x14 | short | 1 | unknown, value = 1 |

| 22/0x16 | short | 1 | unknown, value = 0 |

| 24/0x18 | byte[] | stored at offset 16 | jpeg_data = ffd8ffdb…ffd9 |

| 24+jpeg_size | byte[] | ? | padding to next 4 bytes? |

| long | 1 | ? |

for version 1:

| Offset | type | size | content |

|---|---|---|---|

| 12/0xc | short | 1 | width (160) |

| 14/0xe | short | 1 | height (120) |

| 16/0x10 | long | 1 | jpeg image size (jpeg_size) |

I believe HEIC and AVIF are very similar. However the codec used in AVIF/mdat is royalty free. The HEIC/mdat codec is proprietary. From a metadata standpoint, there’s no apparent difference. The term HEIC is the container for such images. HEIF is the title of the codec technology.

Apple were the first to introduce HEIC files on the iOS devices about 2015. Canon have released cameras with the option to store HEIC. I believe this is an honest effort by Canon to move on from JPEG. Will this be a market success? We don’t know yet. Thanks to Gordon Laing, I have obtained several Canon genenerated HEIC files and I’m very pleased to say that tvisitor required no modification to read the metadata. Thank You, Gordon: https://www.cameralabs.com/tag/heif/

To understand how to parse HEIC and AVIF, we have to discuss the specification of more boxes.

A “Full Box” has a 4 byte header which is version (1 byte) followed by flags (3 bytes). It is specified as follows:

class FullBox(unsigned int(32) boxtype, unsigned int(8) v, bit(24) f)

extends Box(boxtype) {

unsigned int(8) version = v;

bit(24) flags = f;

}Declares the media (handler) type. This effectively add a name for a full box such as ‘pict’.

class HandlerBox extends FullBox(‘hdlr’, version = 0, 0) {

unsigned int(32) pre_defined = 0;

unsigned int(32) handler_type;

const unsigned int(32)[3] reserved = 0;

string name;

}This is the box in which the creator of the file stores the media. From a metadata point of view, there is nothing useful in this box and can be treated as the end of file.

aligned(8) class MediaDataBox extends Box(‘mdat’) {

bit(8) data[];

}This is pure binary data. From a metadata perspective, this the end of the file.

This is specified as follows:

class MetaBox (handler_type)

extends FullBox(‘meta’, version = 0, 0) {

HandlerBox(handler_type) theHandler;

PrimaryItemBox // pitm (optional boxes)

DataInformationBox // dinf

ItemLocationBox // iloc

ItemProtectionBox // iprp

ItemInfoBox // iinf

IPMPControlBox

ItemReferenceBox // iref

ItemDataBox // idat

Box other_boxes[];

}The Item information box provides extra information about selected items, including symbolic (File) names. Effectively is a list of data named data item ID. For our purposes we are interest to know the ID of any Exif metadata.

This is specified as follows:

class ItemInfoBox

extends FullBox(‘iinf’, version, 0) {

if (version == 0) {

unsigned int(16) entry_count;

} else {

unsigned int(32) entry_count;

}

ItemInfoEntry[ entry_count ]

}The item location box provides a directory of resources in this or other Files, by locating their container, their offset within that container, and their length. Placing this in binary format enables common handling of this data, even by systems which do not understand the particular metadata system used.

This is a single box with which contains an array of ID/extent/length tuples. We are very interesting the extend/length of the Exif ID.

Please be aware that the order of the iinf and iloc boxes is not specified. In tvisitor, we parse Exif metadata before we leave the the meta box.

The iloc box is is specified as follows:

class ItemLocationBox

extends FullBox(‘iloc’, version, 0) {

unsigned int(4)

unsigned int(4)

unsigned int(4)

if ((version == 1) || (version == 2)) {

offset_size;

length_size;

base_offset_size;

unsigned int(4) index_size;

} else {

unsigned int(4) reserved;

}

if (version < 2) {

unsigned int(16) item_count;

} else if (version == 2) {

unsigned int(32) item_count;

}

for (i=0; i<item_count; i++) {

if (version < 2) {

unsigned int(16) item_ID;

} else if (version == 2) {

unsigned int(32) item_ID;

}

if ((version == 1) || (version == 2)) {

unsigned int(12) reserved = 0;

unsigned int(4) construction_method;

}

unsigned int(16) data_reference_index;

unsigned int(base_offset_size*8) base_offset;

unsigned int(16) extent_count;

for (j=0; j<extent_count; j++) {

if (((version == 1) || (version == 2)) && (index_size > 0)) {

unsigned int(index_size*8) extent_index;

}

unsigned int(offset_size*8) extent_offset;

unsigned int(length_size*8) extent_length;

} // for j

} // for i

}I obtained HEIC test files from: https://github.com/thorsted/digicam_corpus/tree/master/Apple/iPhone%20XR

I dumped IMG_3578.HEIC with dmpf and disassembled it by hand:

0 0: ___ ftypheic____mif1 -> 00 00 00 20 66 74 79 70 68 65 69 63 00 00 00 00 6d 69 66 31

< length > f t y p < brand > < minor > m i f 1

0x14 20: miafMiHBheic__.4meta -> 6d 69 61 66 4d 69 48 42 68 65 69 63 00 00 0d 34 6d 65 74 61

m i a f M i H B h e i c < length > m e t a

0x28 40: _______.hdlr________ -> 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 22 68 64 6c 72 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00

< version?> < length > h d l r < version > < flags >

0x3c 60: pict________________ -> 70 69 63 74 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00

p i c t < l e

0x50 80: _$dinf___.dref______ -> 00 24 64 69 6e 66 00 00 00 1c 64 72 65 66 00 00 00 00 00 00

ngth> d i n f < length > d r e f

0x64 100: _.___.url ___.___.pi -> 00 01 00 00 00 0c 75 72 6c 20 00 00 00 01 00 00 00 0e 70 69

< length > u r l sp < length > p i

0x78 120: tm_____1__.=iinf____ -> 74 6d 00 00 00 00 00 31 00 00 04 3d 69 69 6e 66 00 00 00 00

t m < length > i i n f < version?>

0x8c 140: _3___.infe.__._.__hv -> 00 33 00 00 00 15 69 6e 66 65 02 00 00 01 00 01 00 00 68 76

< E#> < length > i n f e < V > <flag>< ID> h v

0xa0 160: c1____.infe.__._.__h -> 63 31 00 00 00 00 15 69 6e 66 65 02 00 00 01 00 02 00 00 68

c 1 < length > i n f e

0xb4 180: vc1____.infe.__._.__ -> 76 63 31 00 00 00 00 15 69 6e 66 65 02 00 00 01 00 03 00 00

...

0x44c 1100: .__hvc1____.infe.__. -> 2e 00 00 68 76 63 31 00 00 00 00 15 69 6e 66 65 02 00 00 01

0x460 1120: _/__hvc1____.infe.__ -> 00 2f 00 00 68 76 63 31 00 00 00 00 15 69 6e 66 65 02 00 00

0x49c 1180: ____2__hvc1____.infe -> 00 00 00 00 32 00 00 68 76 63 31 00 00 00 00 15 69 6e 66 65

< length > i n f e

0x4b0 1200: .__._3__Exif____.ire -> 02 00 00 01 00 33 00 00 45 78 69 66 00 00 00 00 94 69 72 65

< V > <flag>< ID> <pro> E x i fnul < length > i r e

0x4c4 1220: f_______ldimg_1_0_._ -> 66 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 6c 64 69 6d 67 00 31 00 30 00 01 00

f

0x4d8 1240: ._._._._._._._._._._ -> 02 00 03 00 04 00 05 00 06 00 07 00 08 00 09 00 0a 00 0b 00

...

0xa14 2580: __.@iloc.___D__3_.__ -> 00 00 03 40 69 6c 6f 63 01 00 00 00 44 00 00 33 00 01 00 00

< length > i l o c < FullBox > <o-l> <-#E> < ID> < CM>

0xa28 2600: ___.__*.__.._._____. -> 00 00 00 01 00 00 2a b3 00 00 2e a7 00 02 00 00 00 00 00 01

<DRI> <OFF> <EXC> 10931 < ??> 11943 < ID> < CM> <DRI> <OFF>

0xa3c 2620: __YZ__`._._____.__.K -> 00 00 59 5a 00 00 60 f1 00 03 00 00 00 00 00 01 00 00 ba 4b

<EXC> 22874 ? ? 24817 < ID> < CM> <DRI> <OFF> <EXC> 47691

0xa50 2640: __N._._____._...__K. -> 00 00 4e 8e 00 04 00 00 00 00 00 01 00 01 08 d9 00 00 4b f9

0xa64 2660: _._____._.T.__M._.__ -> 00 05 00 00 00 00 00 01 00 01 54 d2 00 00 4d 02 00 06 00 00

0xa78 2680: ___._...__N._._____. -> 00 00 00 01 00 01 a1 d4 00 00 4e ff 00 07 00 00 00 00 00 01

0xa8c 2700: _...__F._._____._.7. -> 00 01 f0 d3 00 00 46 cc 00 08 00 00 00 00 00

EXC = extent_count CM = construction_method #E = Number of Entries DRI = data_reverence_index

OFF = base_offset o-l = offset-length ID = IndentifierThe code in ISOBMFF/iloc.cpp is (effectively):

void ILOC::ReadData( Parser & parser, BinaryStream & stream )

{

FullBox::ReadData( parser, stream );

uint8_t u8 = stream.ReadUInt8();

this->SetOffsetSize( u8 >> 4 );

this->SetLengthSize( u8 & 0xF );

u8 = stream.ReadUInt8();

this->SetBaseOffsetSize( u8 >> 4 );

this->SetIndexSize( u8 & 0xF );

uint32_t count = this->GetVersion() < 2 ) ?stream.ReadBigEndianUInt16() : stream.ReadBigEndianUInt32();

this->impl->_items.clear();

for( uint32_t i = 0; i < count; i++ )

{

this->AddItem( std::make_shared< Item >( stream, *( this ) ) );

}

}When processed by tvisitor, we see:

$ tvisitor ~/Downloads/IMG_3578.HEIC

STRUCTURE OF JP2 (heic) FILE (MM): /Users/rmills/Downloads/IMG_3578.HEIC

address | length | box | uuid | data

0 | 24 | ftyp | | heic____mif1miafMiHB

32 | 3372 | meta | | _______.hdlr________ 'meta' box

STRUCTURE OF JP2 FILE (MM): /Users/rmills/Downloads/IM

0 | 26 | hdlr | | ________pict______

34 | 28 | dinf | | ___.dref_______.__ 'meta/dinf' box

STRUCTURE OF JP2 FILE (MM): /Users/rmills/Downloads/

0 | 20 | dref | | _______.___.url

END: /Users/rmills/Downloads/IMG_3578.HEIC:44->3368:

70 | 6 | pitm | | _____1 0 0 0 0 0 4

84 | 1077 | iinf | | _____3___.infe.__. 'meta/dinf/iinf' box

STRUCTURE OF JP2 FILE (MM): /Users/rmills/Downloads/

0 | 13 | infe | | .__._.__hvc1_ 'meta/dinf/iinf/infe' boxes

...

1050 | 13 | infe | | .__._3__Exif_ ID==51 "Exif\0"

END: /Users/rmills/Downloads/IMG_3578.HEIC:44->3368:

1169 | 140 | iref | | _______ldimg_1_0_.

1317 | 1195 | iprp | | __.lipco__.0colrpr

STRUCTURE OF JP2 FILE (MM): /Users/rmills/Downloads/

0 | 868 | ipco | | __.0colrprof__.$

STRUCTURE OF JP2 FILE (MM): /Users/rmills/Download

0 | 552 | colr | | prof__.$appl._

560 | 104 | hvcC | | ..p___._____Z.

672 | 12 | ispe | | ______.___._ 0

692 | 12 | ispe | | ______..__.. 0

712 | 1 | irot | | _ 0

721 | 8 | pixi | | ____.... 0 0 0

737 | 103 | hvcC | | ..p___._____<.

848 | 12 | ispe | | ______.@___. 0

END: /Users/rmills/Downloads/IMG_3578.HEIC:44->336

876 | 311 | ipma | | _______2_....._.

END: /Users/rmills/Downloads/IMG_3578.HEIC:44->3368:

2520 | 8 | idat | | __...... 0 0 5 7 1

2536 | 824 | iloc | | .___D__3_._____.__ 'meta/dinf/iloc' box

2544 | 16 | ext | 1 | 10931, 11943 iloc is a binary array

...

3344 | 16 | ext | 51 | 8907, 2024 ID==51 offset/length

END: /Users/rmills/Downloads/IMG_3578.HEIC:44->3368

3412 | -7 | mdat | | _____...__.c(........ 'mdat' box (EOF)

STRUCTURE OF TIFF FILE (MM): /Users/rmills/Downloads/IM Dump the embedded Exif/TIFF

address | tag | t

10 | 0x010f Exif.Image.Make | AS

22 | 0x0110 Exif.Image.Model | AS

...

END: /Users/rmills/Downloads/IMG_3578.HEIC:8917->2014

END: /Users/rmills/Downloads/IMG_3578.HEIC:8917->2014

END: /Users/rmills/Downloads/IMG_3578.HEICThe tvisitor.cpp code is a structural parser. It locates Exif metadata within the meta box and, if the user has selected the Recursive option (-pR), will report the Exif metadata. However, the kpsBasic report can report boxes as metadata and this has been done for the ispe box which is specified as follows:

class Box (unsigned int(32) boxtype,

optional unsigned int(8)[16] extended_type) {

unsigned int(32) size;

unsigned int(32) type = boxtype;

if (size==1) {

unsigned int(64) largesize;

} else if (size==0) {

// box extends to end of file

}

if (boxtype==‘uuid’) {

unsigned int(8)[16] usertype = extended_type;

}

}

class FullBox(unsigned int(32) boxtype,

unsigned int(8) v, bit(24) f) extends Box(boxtype) {

unsigned int(8) version = v;

bit(24) flags = f;

}

class ImageSpatialExtentsProperty

extends ItemFullProperty('ispe', version = 0, flags = 0) {

unsigned int(32) image_width;

unsigned int(32) image_height;

}This is coded into tvisitor.cpp as follows:

// BMFF boxes

boxDict["ispe"] = "BMFF.ispe";

boxTags["ispe"].push_back(Field("Version" ,kttUShort , 0, 1));

boxTags["ispe"].push_back(Field("Flags" ,kttUByte , 1, 3));

boxTags["ispe"].push_back(Field("Width" ,kttLong , 4, 1));

boxTags["ispe"].push_back(Field("Height" ,kttLong , 8, 1));The processing of this data is achieved in ReportVisitor::visitBox() as follows:

if ( boxDict.find(name) != boxDict.end() ) {

if ( boxTags.find(name) != boxTags.end() ) {

for (Field field : boxTags[name] ) {

std::string n = chop( boxDict[name] + "." + field.name(),28);

endian_e endian = field.endian() == keImage ? image.endian() : field.endian();

out() << indent() << stringFormat("%-28s ",n.c_str())

<< chop(data.toString(field.type(),field.count(),endian,field.start()),40)

<< std::endl;

}

}

}These tags are reported as metadata as follows:

0 | 20 | ispe | | ______..__.. 0 0 0 0 0 0 15 160 0 0 23 128

BMFF.ispe.Version 0

BMFF.ispe.Flags 0 0 0

BMFF.ispe.Width 4000

BMFF.ispe.Height 6016More information about binary decoding in tvisitor.cpp is discussed in 3.5 ReportVisitor::visitTag()

The JXL format is the current contendor to replace JPEG/GIF as the most popular image format. At the time of writing (2021), it is too early to say if it will reach the goal that eluded PNG, JP2 and WebP. There is a discussion of this format here: https://github.com/Exiv2/exiv2/issues/1503.

JPEG-XL is the only format discussed in this book which has two file layouts. The first format is naked codestream JXL. The first two bytes are 0xff0a. I have no further information about this stream. It does not contain Exif, IPTC or XML data. However it does contain the image and related data such as size, orientation and color profile/handler.

...book $ dmpf count=20 files/jxl.jxl

0 0: .......'.#J....EQ._. -> ff 0a fa bb e8 f3 e1 27 85 23 4a 01 03 0a 10 45 51 14 00 08